Working as a group of three, we imagined a world in which technological advancements allow for healthcare from home. A series of regular kitchen objects deliver medicine, and measure the user’s biological and behavioural trends, relaying this information to the patient and their GP. In the context of ‘living beyond cancer’, this acts to treat and monitor the risk of readmission.

I then took this on as an individual project, delving further into these dining objects and their communication with their user.

Working as a group of three, we imagined a world in which technological advancements allow for healthcare from home. A series of regular kitchen objects deliver medicine, and measure the user’s biological and behavioural trends, relaying this information to the patient and their GP. In the context of ‘living beyond cancer’, this acts to treat and monitor the risk of readmission.

I then took this on as an individual project, delving further into these dining objects and their communication with their user.

Working as a group of three, we imagined a world in which technological advancements allow for healthcare from home. A series of regular kitchen objects deliver medicine, and measure the user’s biological and behavioural trends, relaying this information to the patient and their GP. In the context of ‘living beyond cancer’, this acts to treat and monitor the risk of readmission.

I then took this on as an individual project, delving further into these dining objects and their communication with their user.

Discover

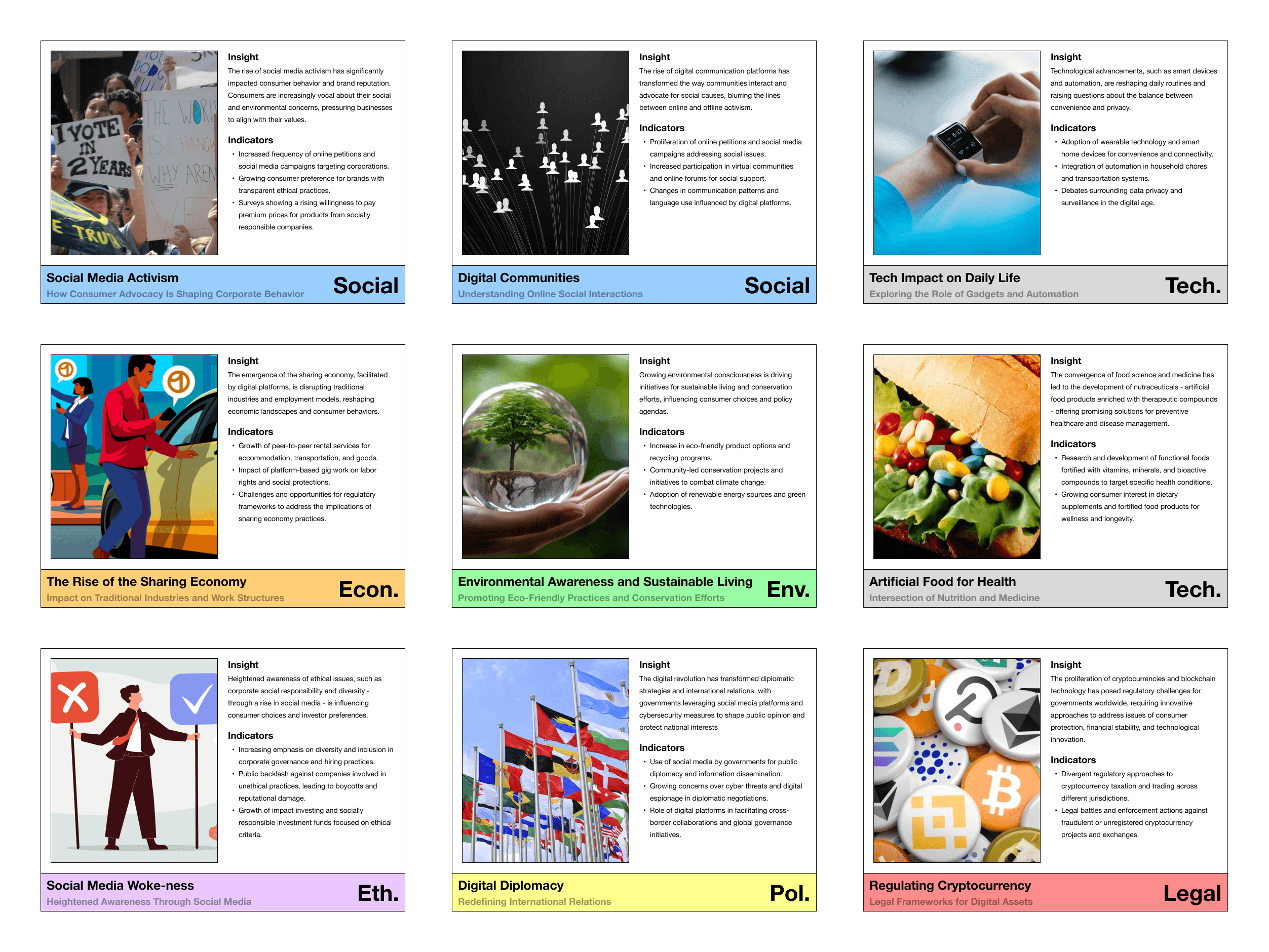

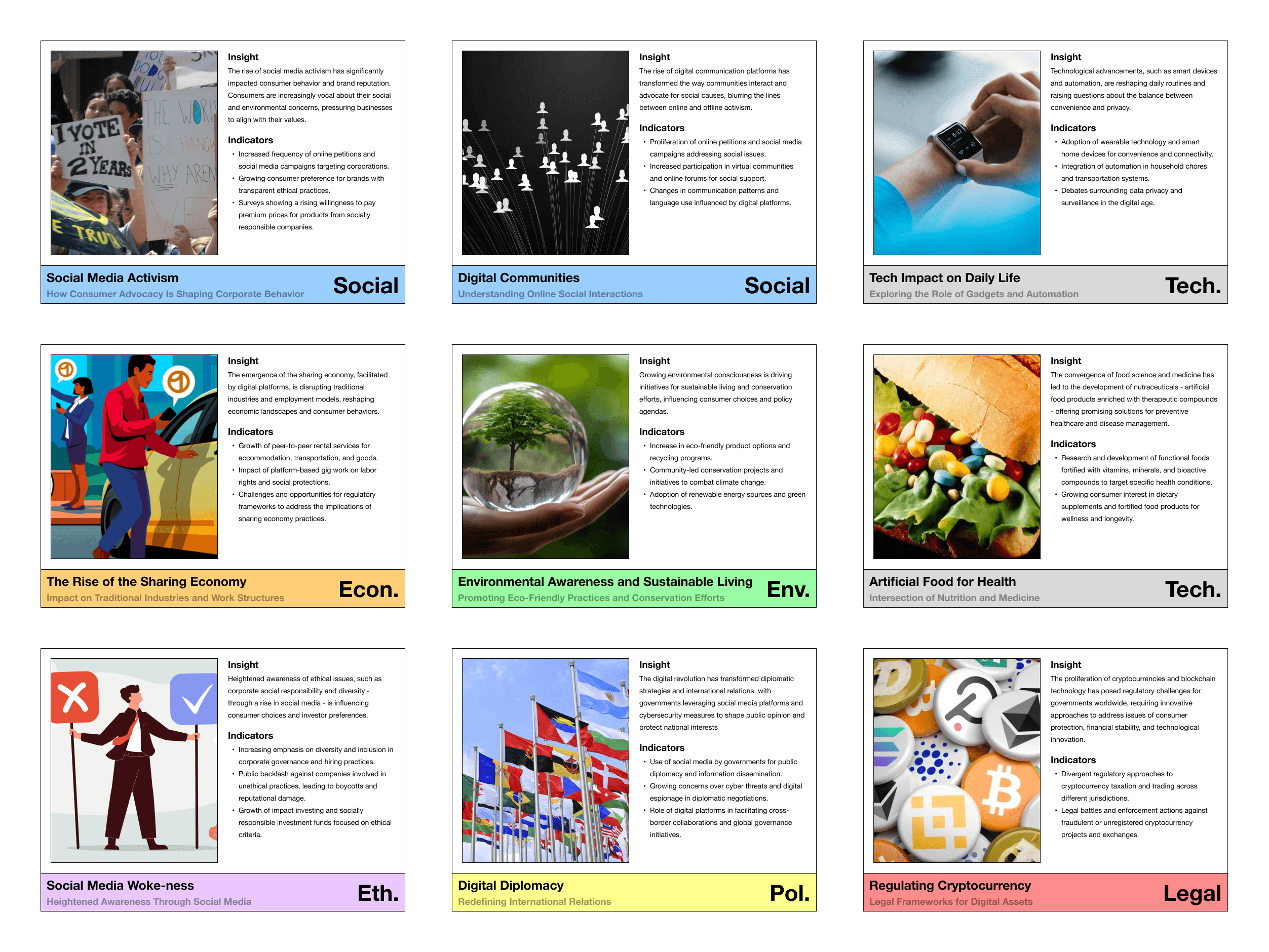

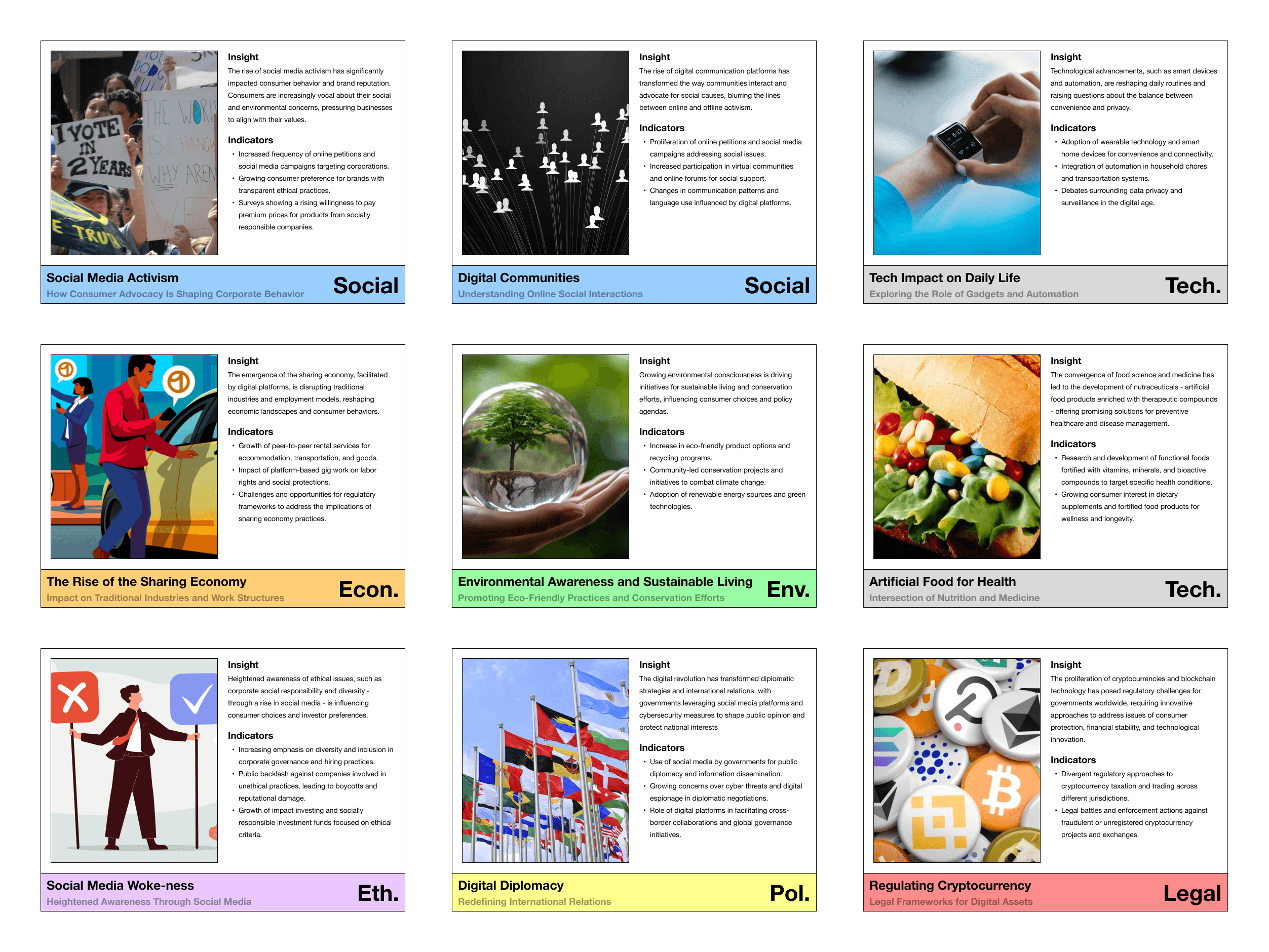

During the initial phase of the project - spanning three weeks - we were to construct a 2030 world around our key themes of ‘living beyond cancer’, ‘collective intelligence’, and ‘big data’.

To begin this process, we first performed a STEEPLE investigation. This involved identifying various social, technological, economic, environmental, political, legal, and ethical factors, which acted as a basis for exploration as we headed into speculative design workshops.

Discover

During the initial phase of the project - spanning three weeks - we were to construct a 2030 world around our key themes of ‘living beyond cancer’, ‘collective intelligence’, and ‘big data’.

To begin this process, we first performed a STEEPLE investigation. This involved identifying various social, technological, economic, environmental, political, legal, and ethical factors, which acted as a basis for exploration as we headed into speculative design workshops.

Discover

During the initial phase of the project - spanning three weeks - we were to construct a 2030 world around our key themes of ‘living beyond cancer’, ‘collective intelligence’, and ‘big data’.

To begin this process, we first performed a STEEPLE investigation. This involved identifying various social, technological, economic, environmental, political, legal, and ethical factors, which acted as a basis for exploration as we headed into speculative design workshops.

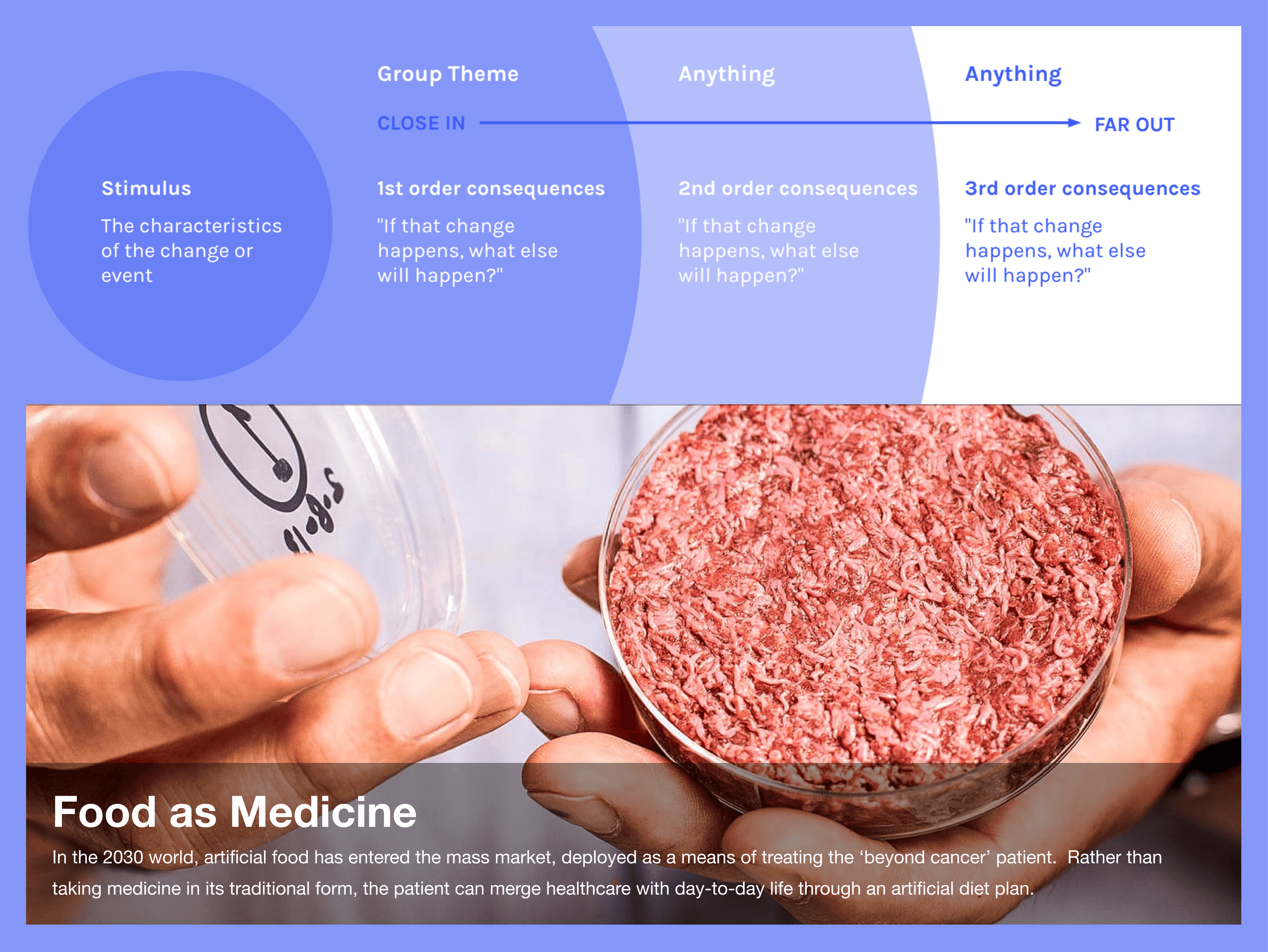

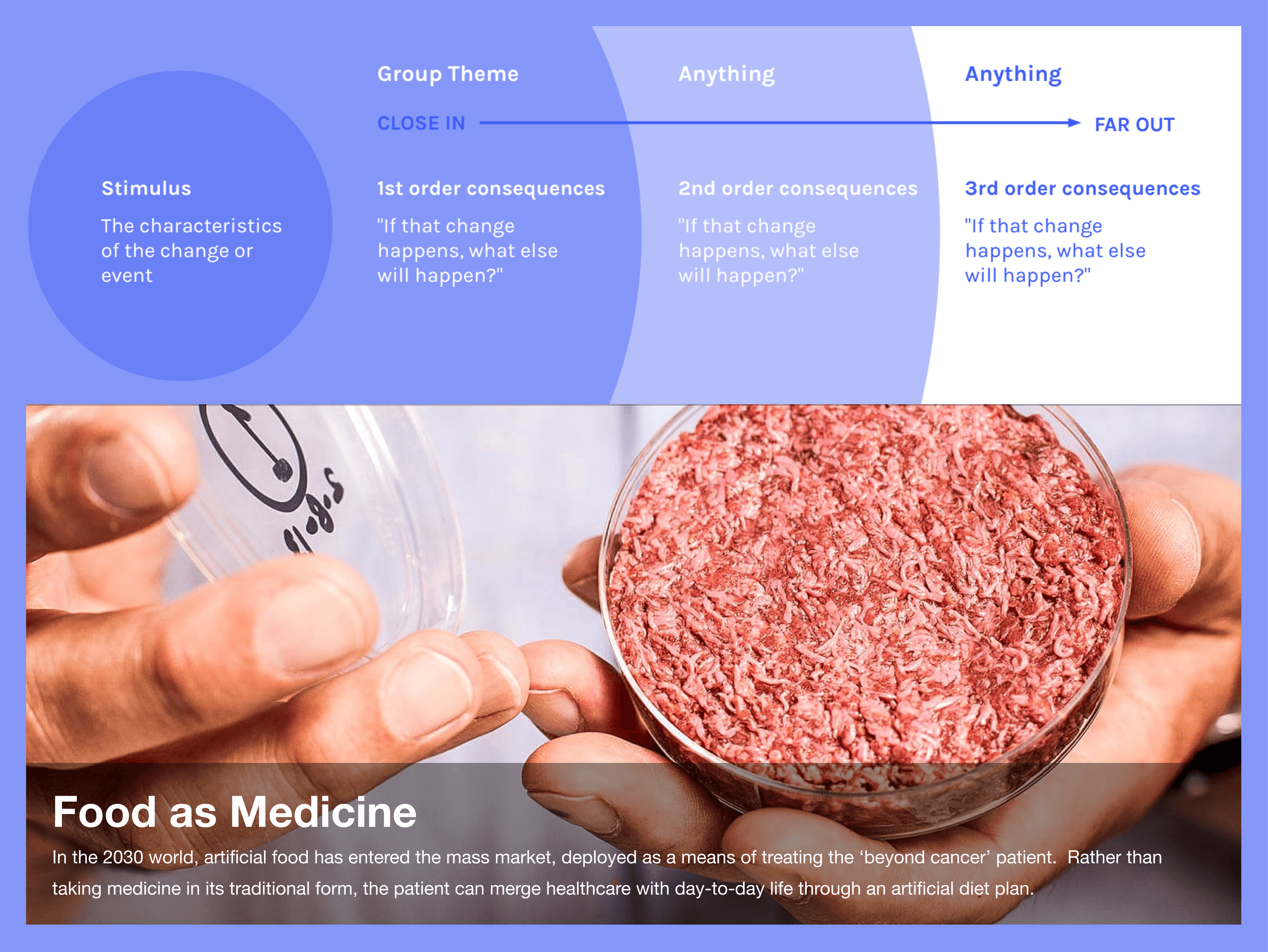

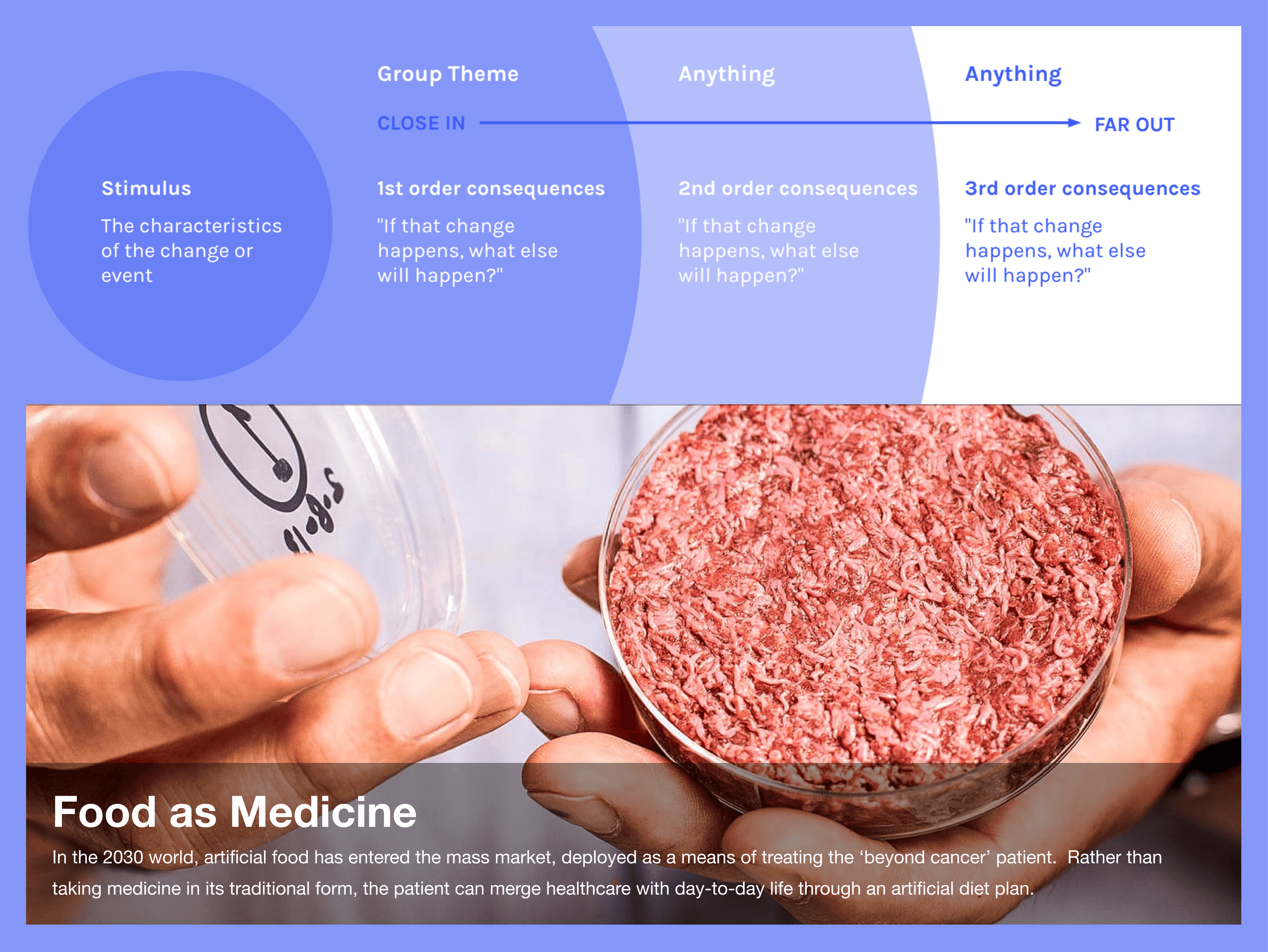

The most valuable of these workshops was ‘Unintended Consequences’, led by design studio AndThen. This provided a structure for investigating change; we were to take some of the initial factors identified through the STEEPLE investigation, and work through ‘so what, if what, then what’ scenarios to anticipate how these might evolve over the next ten years.

These processes helped us imagine a future scenario; advancements in food science and technology are making it increasingly feasible to incorporate medicines into food, whilst maintaining their effectiveness and stability.

The most valuable of these workshops was ‘Unintended Consequences’, led by design studio AndThen. This provided a structure for investigating change; we were to take some of the initial factors identified through the STEEPLE investigation, and work through ‘so what, if what, then what’ scenarios to anticipate how these might evolve over the next ten years.

These processes helped us imagine a future scenario; advancements in food science and technology are making it increasingly feasible to incorporate medicines into food, whilst maintaining their effectiveness and stability.

The most valuable of these workshops was ‘Unintended Consequences’, led by design studio AndThen. This provided a structure for investigating change; we were to take some of the initial factors identified through the STEEPLE investigation, and work through ‘so what, if what, then what’ scenarios to anticipate how these might evolve over the next ten years.

These processes helped us imagine a future scenario; advancements in food science and technology are making it increasingly feasible to incorporate medicines into food, whilst maintaining their effectiveness and stability.

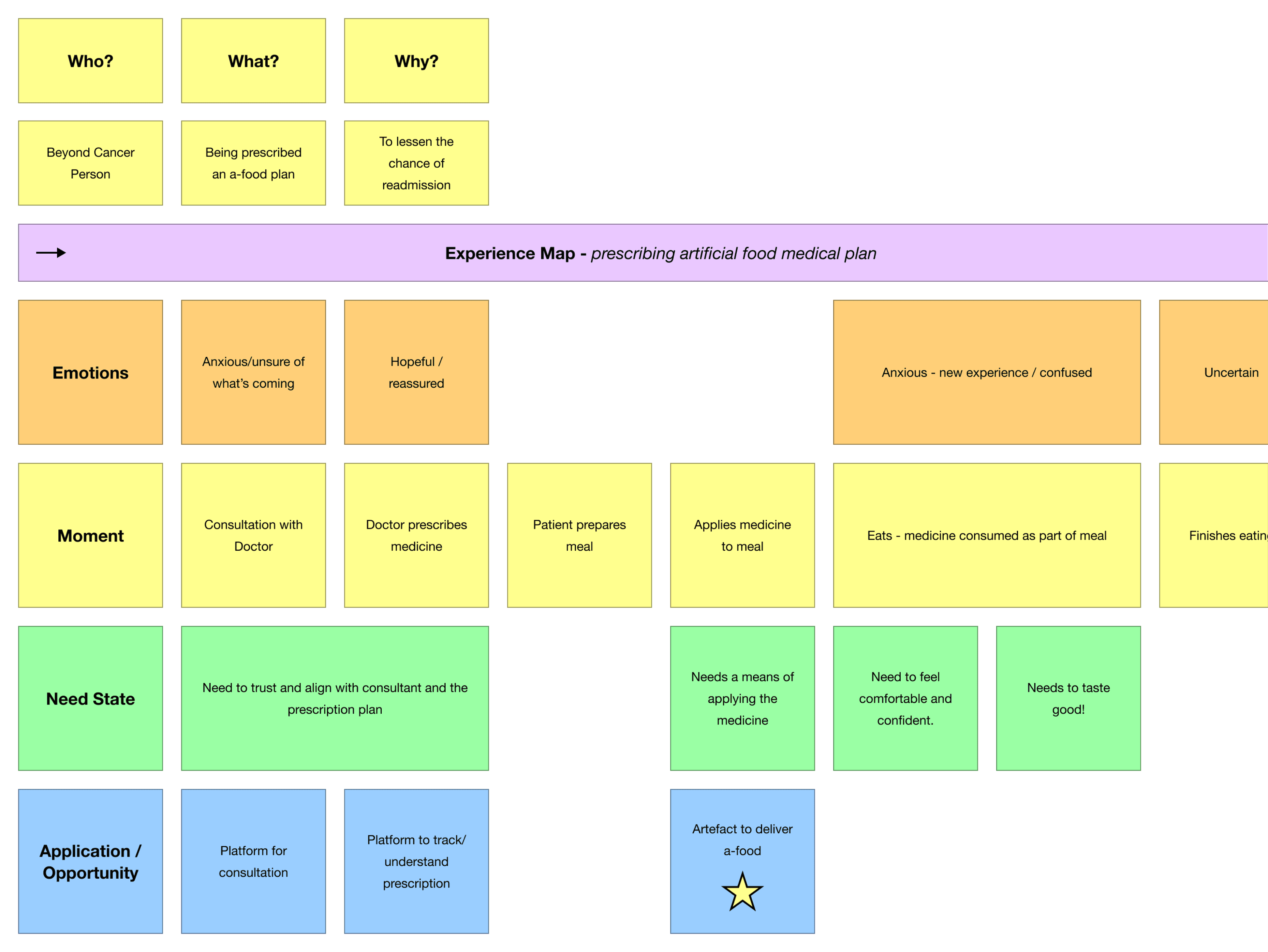

Define

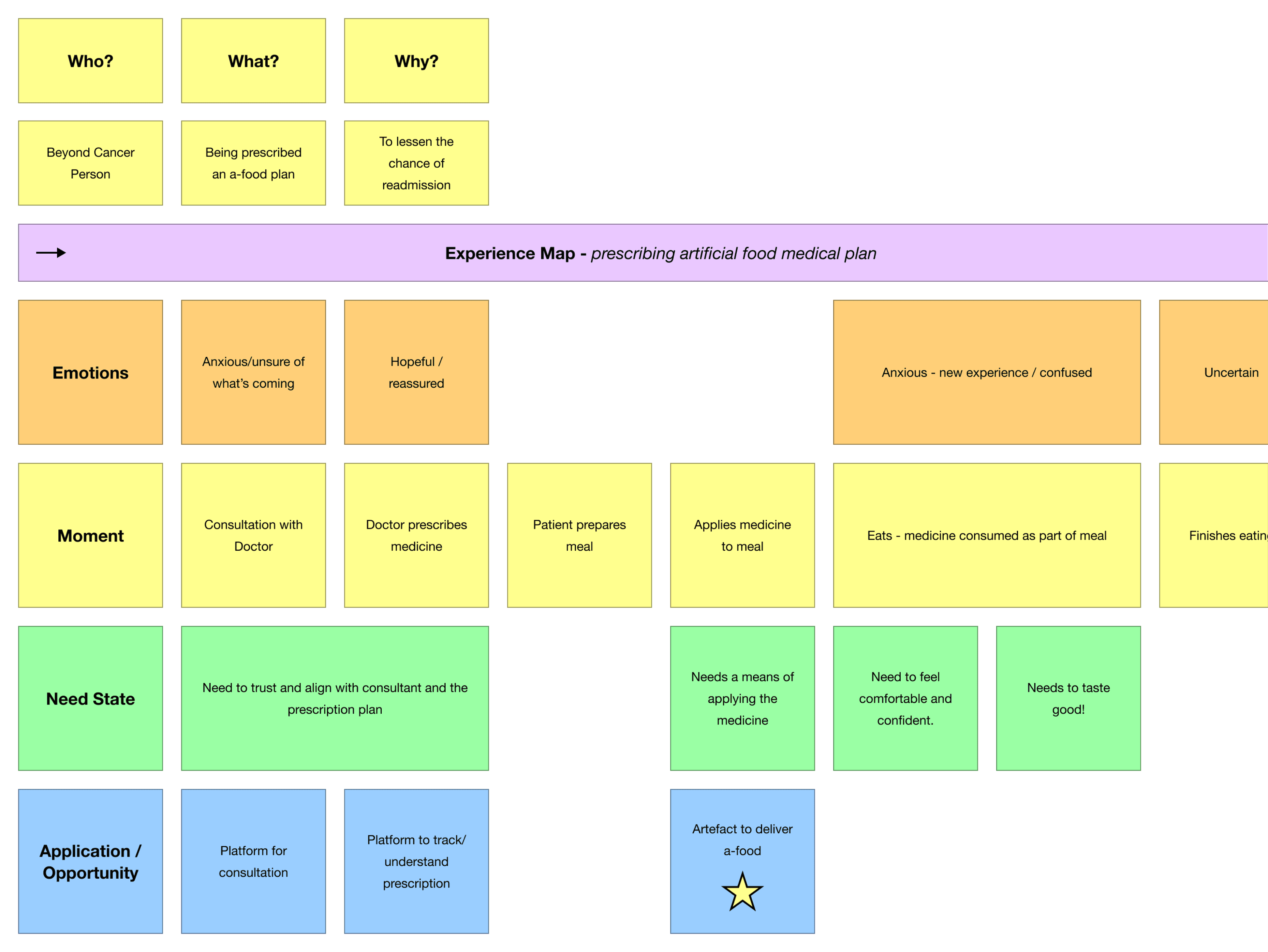

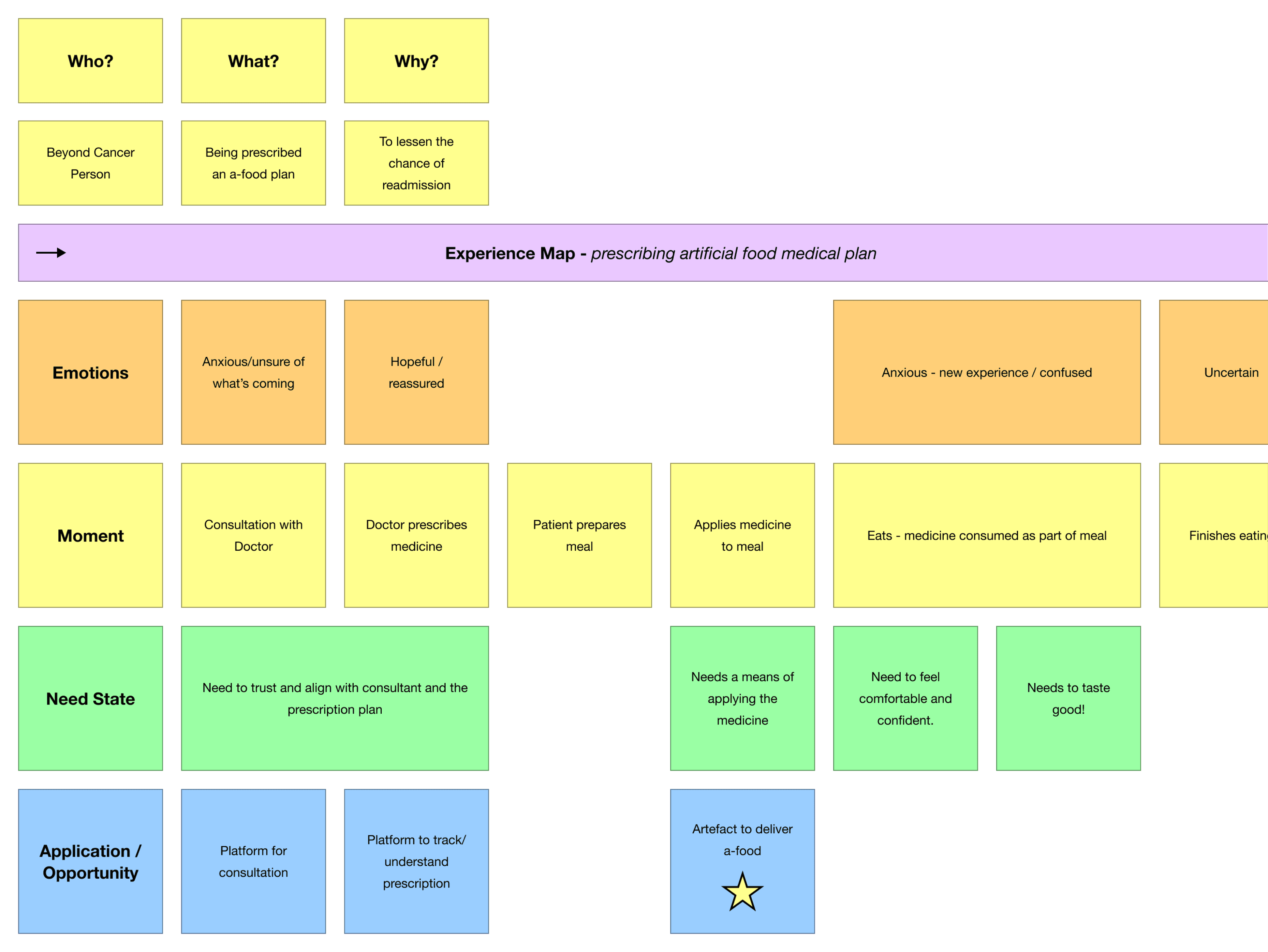

We now had a broad concept around medicine becoming part of the dining ritual.

In order to further define this concept, we created experience maps - which outlined a scenario in which medicine was taken as part of the ‘beyond cancer’ person’s meal - mapping the various moments, emotions, need states, and design opportunities.

It was here that we realised the opportunity for an artefact to apply medicine to the patient’s food.

We were then able to discuss our concept with professionals from Glasgow University’s Institute of Cancer Science, as part of an expert session. They confirmed that our idea was within reason, and reminded us to think beyond the individual user - how might the system play to many people living beyond cancer?

Define

We now had a broad concept around medicine becoming part of the dining ritual.

In order to further define this concept, we created experience maps - which outlined a scenario in which medicine was taken as part of the ‘beyond cancer’ person’s meal - mapping the various moments, emotions, need states, and design opportunities.

It was here that we realised the opportunity for an artefact to apply medicine to the patient’s food.

We were then able to discuss our concept with professionals from Glasgow University’s Institute of Cancer Science, as part of an expert session. They confirmed that our idea was within reason, and reminded us to think beyond the individual user - how might the system play to many people living beyond cancer?

Define

We now had a broad concept around medicine becoming part of the dining ritual.

In order to further define this concept, we created experience maps - which outlined a scenario in which medicine was taken as part of the ‘beyond cancer’ person’s meal - mapping the various moments, emotions, need states, and design opportunities.

It was here that we realised the opportunity for an artefact to apply medicine to the patient’s food.

We were then able to discuss our concept with professionals from Glasgow University’s Institute of Cancer Science, as part of an expert session. They confirmed that our idea was within reason, and reminded us to think beyond the individual user - how might the system play to many people living beyond cancer?

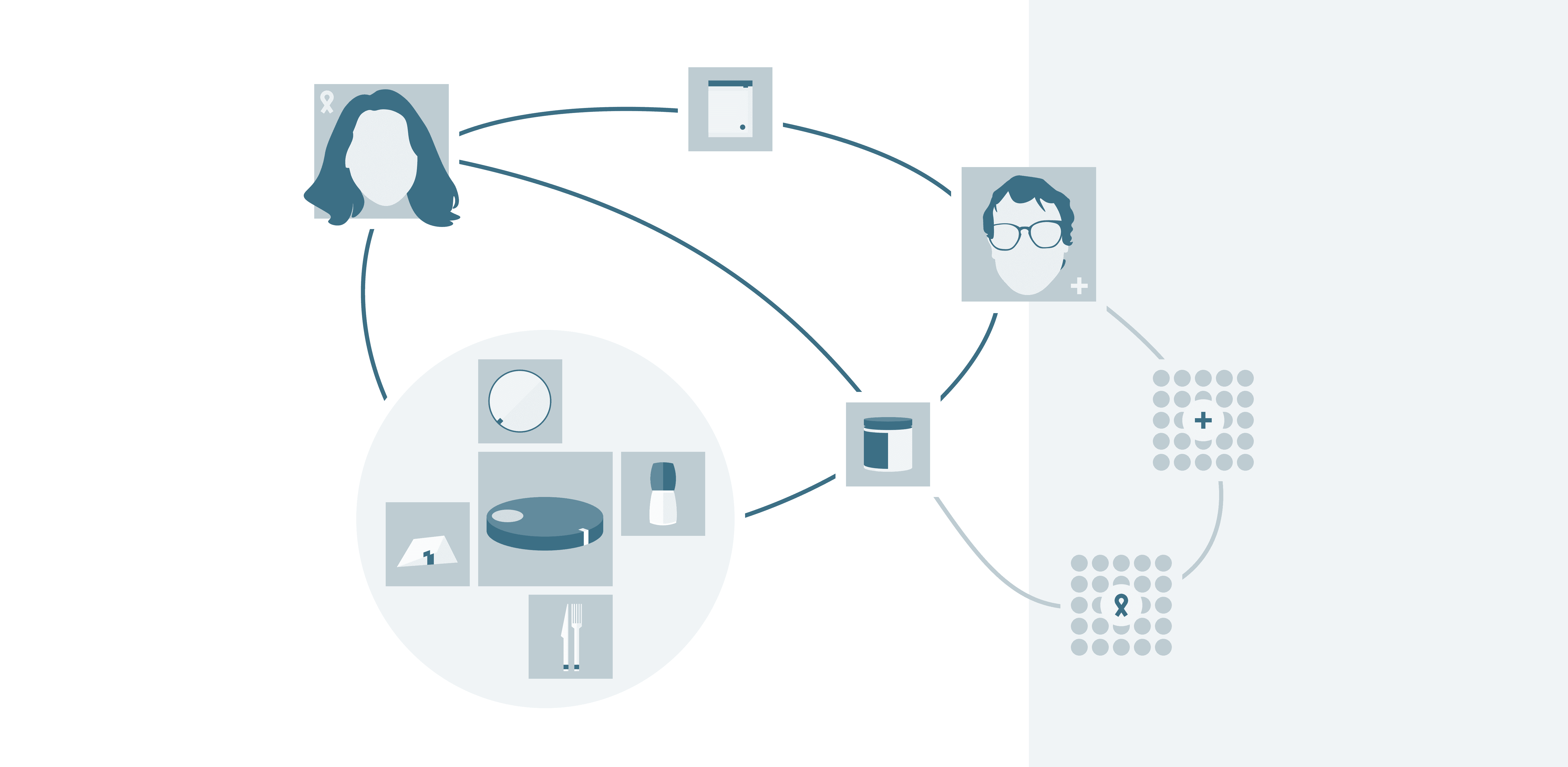

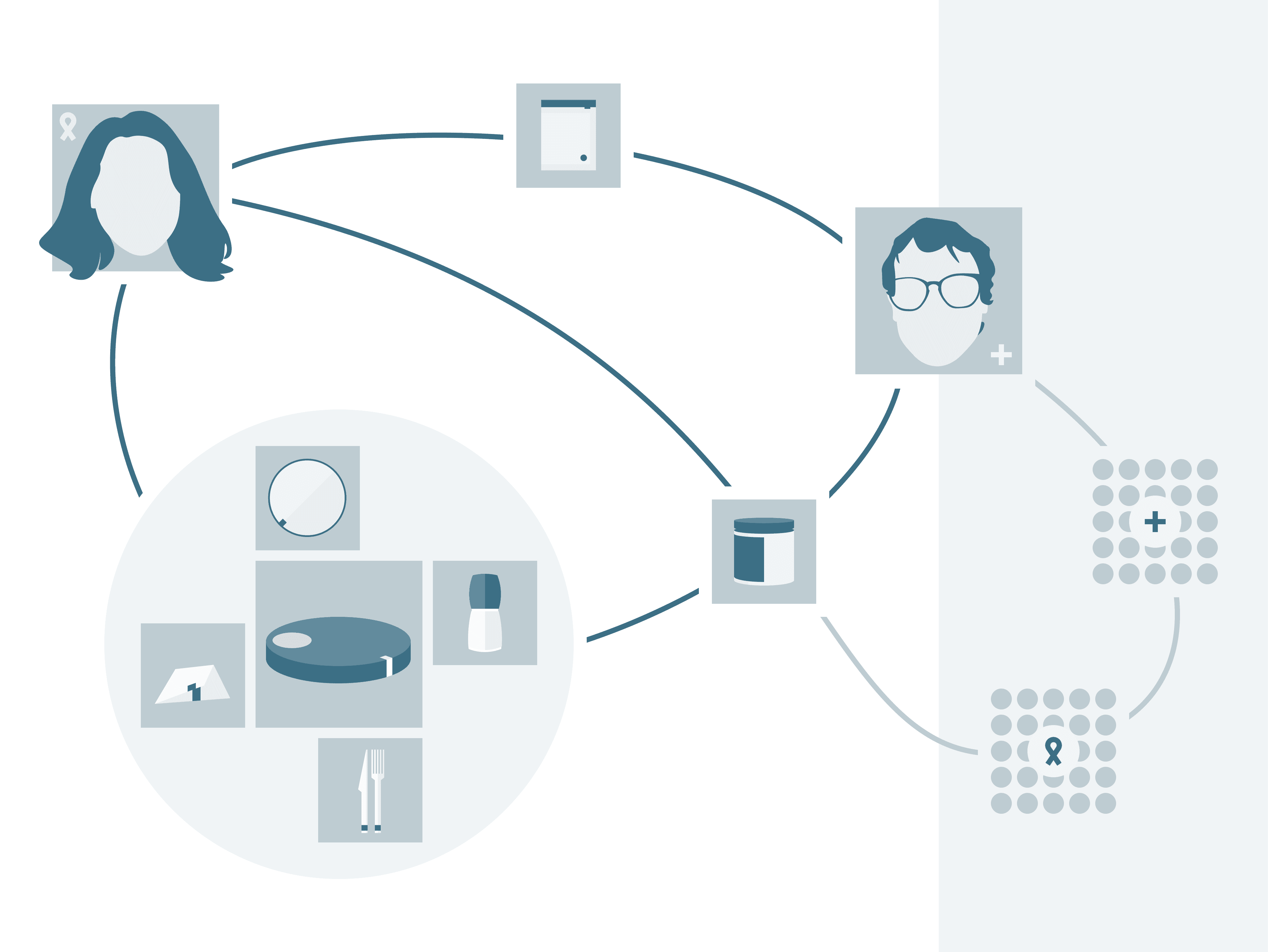

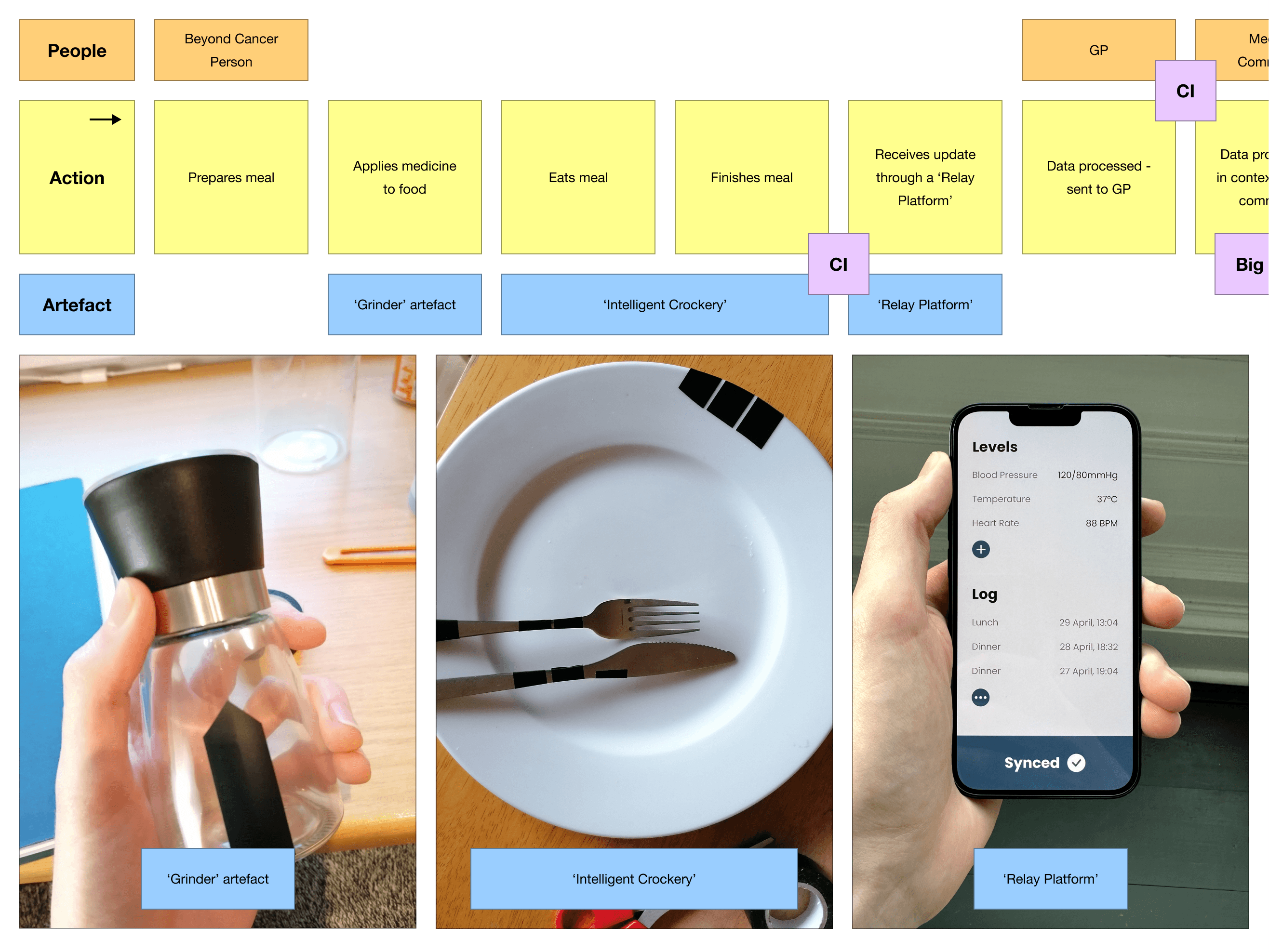

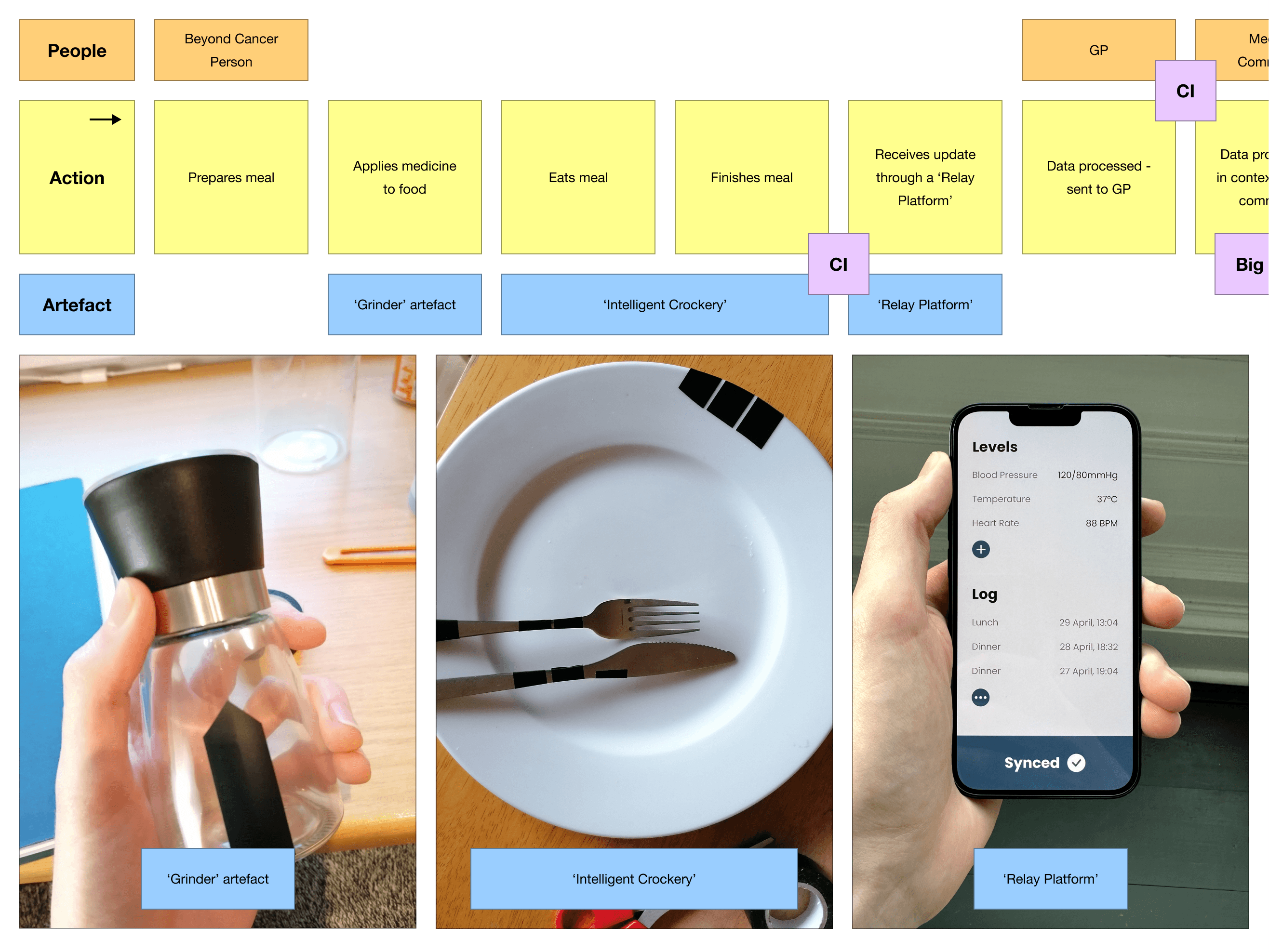

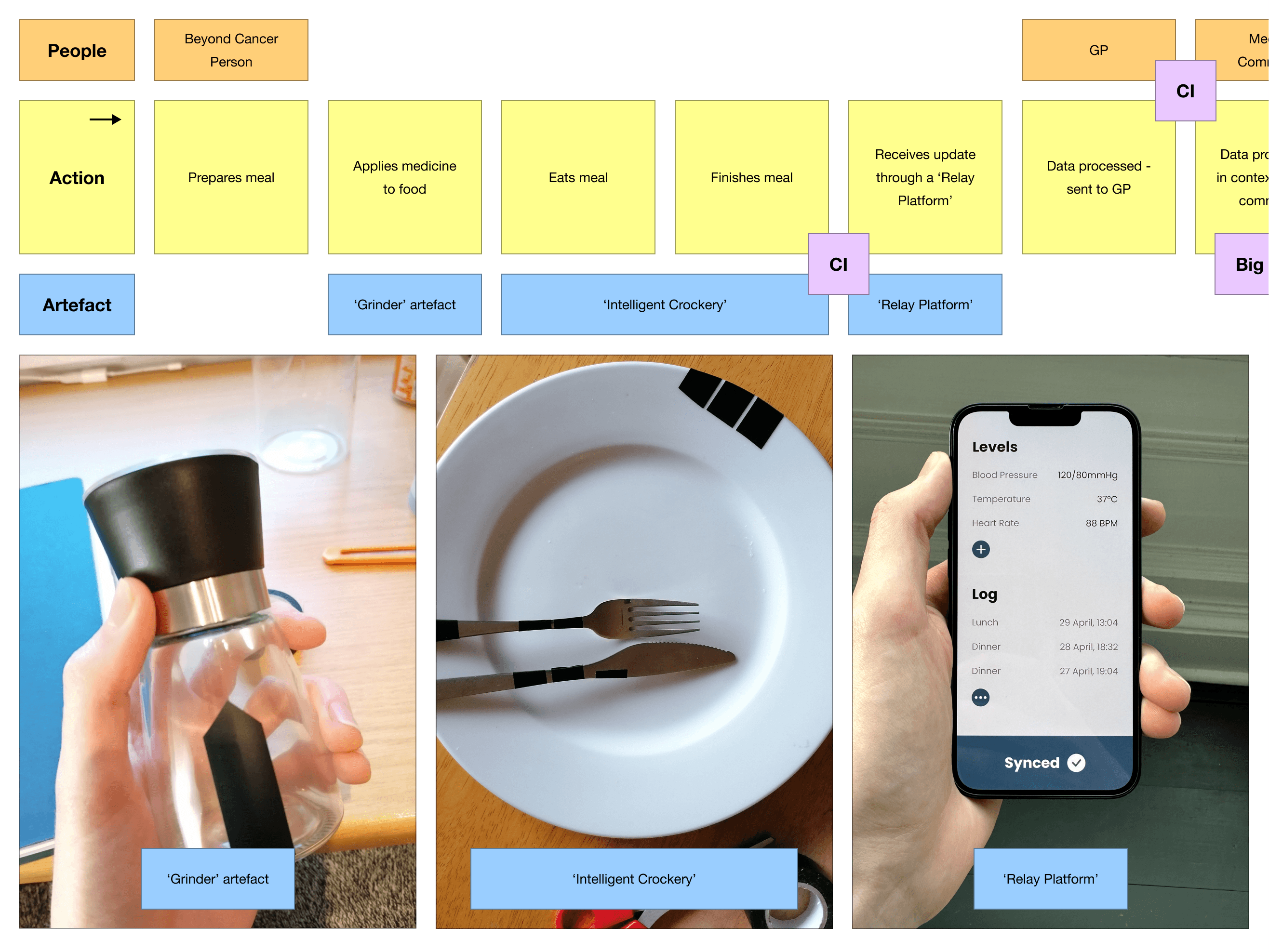

Develop

To think about the wider role of the system, and ensure relevance to the themes of ‘big data’ and ‘collective intelligence’, we spent some time discussing as a group.

In referring to the experience map, we realised the opportunity for additional artefacts; other dining objects might act as monitoring devices - measuring the patient’s biological levels, and relaying this information to the patient and their GP.

Together the artefacts would act to deliver medicine and monitor the patient’s health. In a broader context, the data gathered from many users might help identify patterns and trends; leveraging big data to better understand the individual’s risk of cancer readmission.

Develop

To think about the wider role of the system, and ensure relevance to the themes of ‘big data’ and ‘collective intelligence’, we spent some time discussing as a group.

In referring to the experience map, we realised the opportunity for additional artefacts; other dining objects might act as monitoring devices - measuring the patient’s biological levels, and relaying this information to the patient and their GP.

Together the artefacts would act to deliver medicine and monitor the patient’s health. In a broader context, the data gathered from many users might help identify patterns and trends; leveraging big data to better understand the individual’s risk of cancer readmission.

Develop

To think about the wider role of the system, and ensure relevance to the themes of ‘big data’ and ‘collective intelligence’, we spent some time discussing as a group.

In referring to the experience map, we realised the opportunity for additional artefacts; other dining objects might act as monitoring devices - measuring the patient’s biological levels, and relaying this information to the patient and their GP.

Together the artefacts would act to deliver medicine and monitor the patient’s health. In a broader context, the data gathered from many users might help identify patterns and trends; leveraging big data to better understand the individual’s risk of cancer readmission.

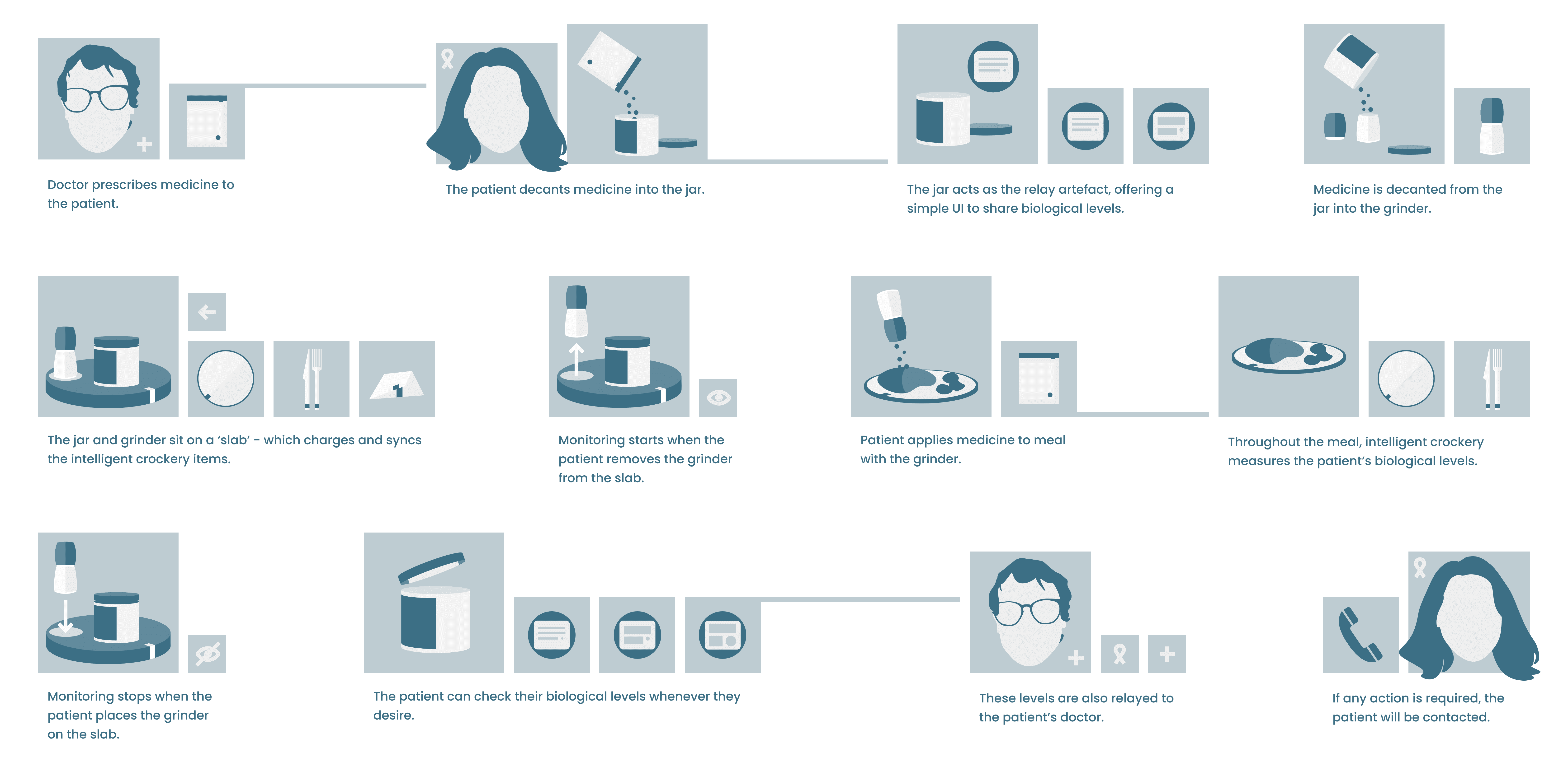

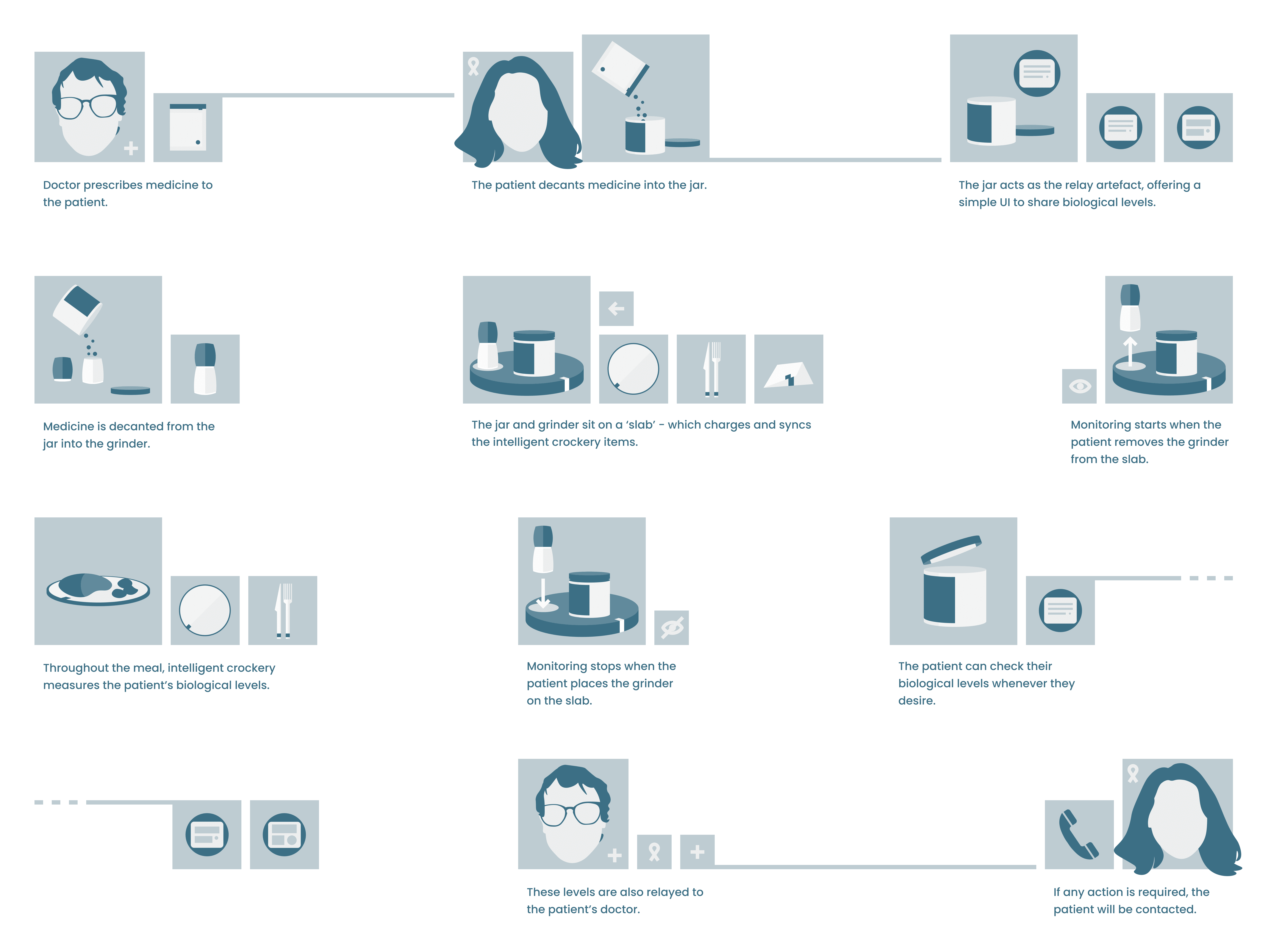

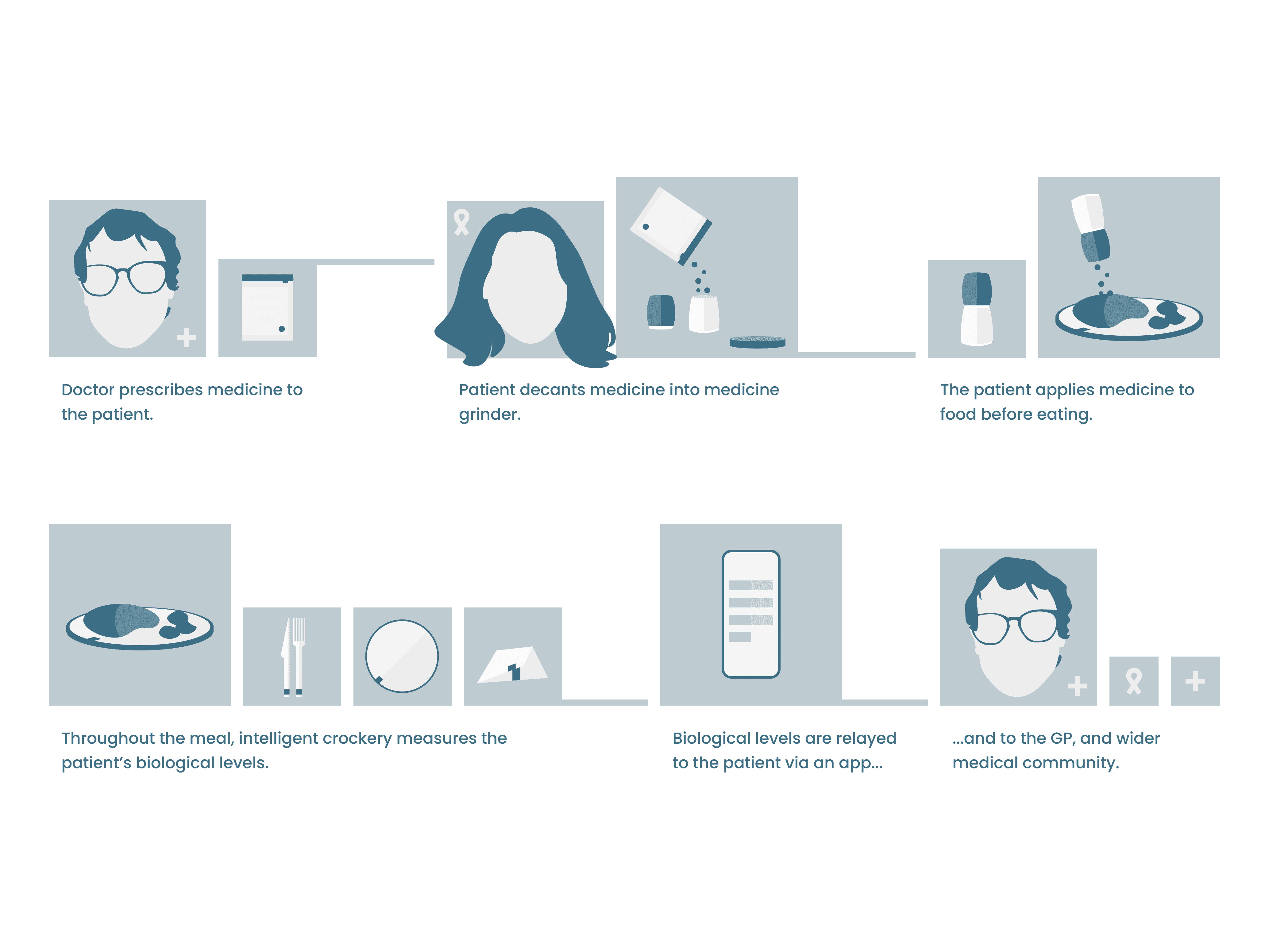

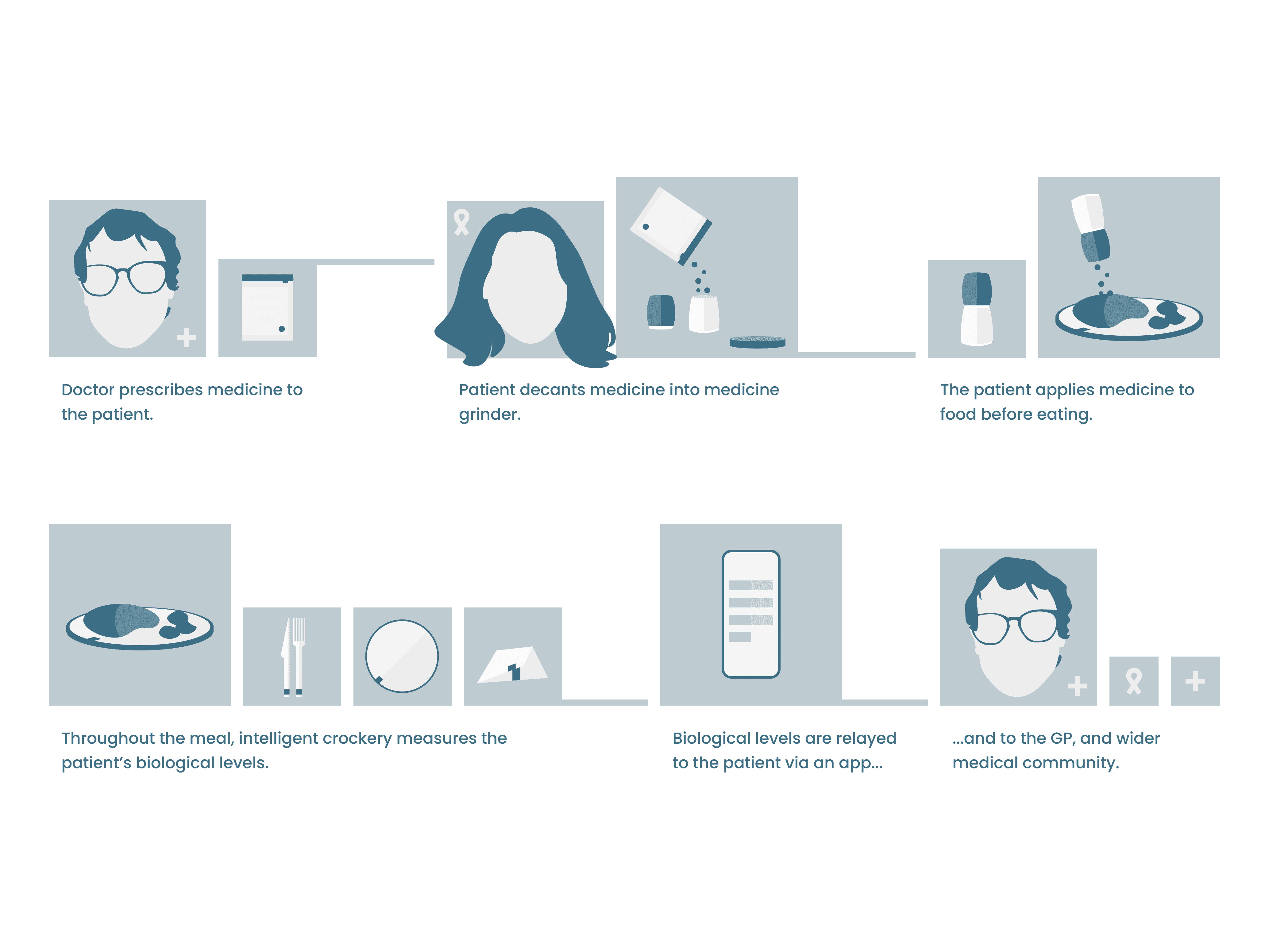

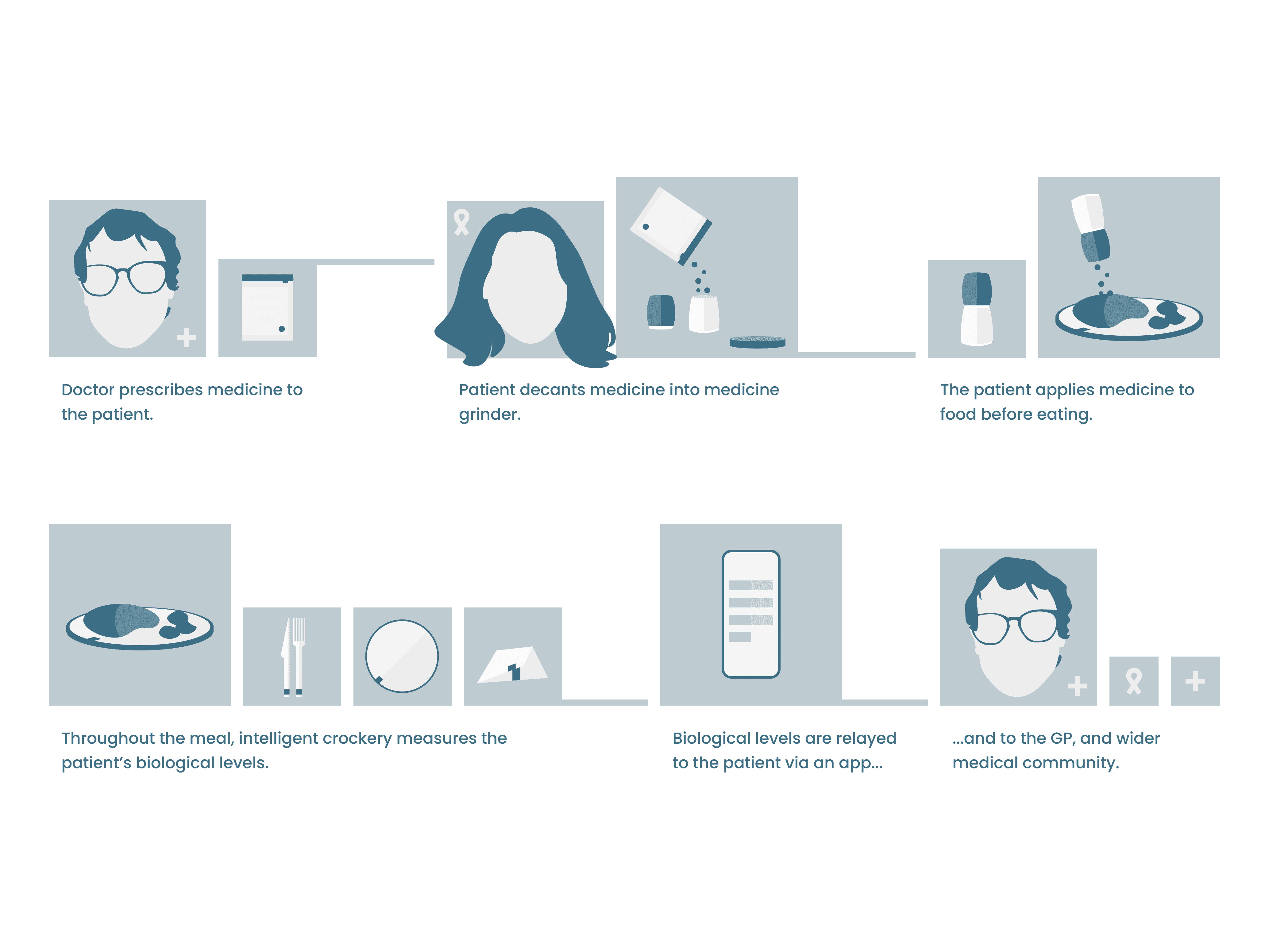

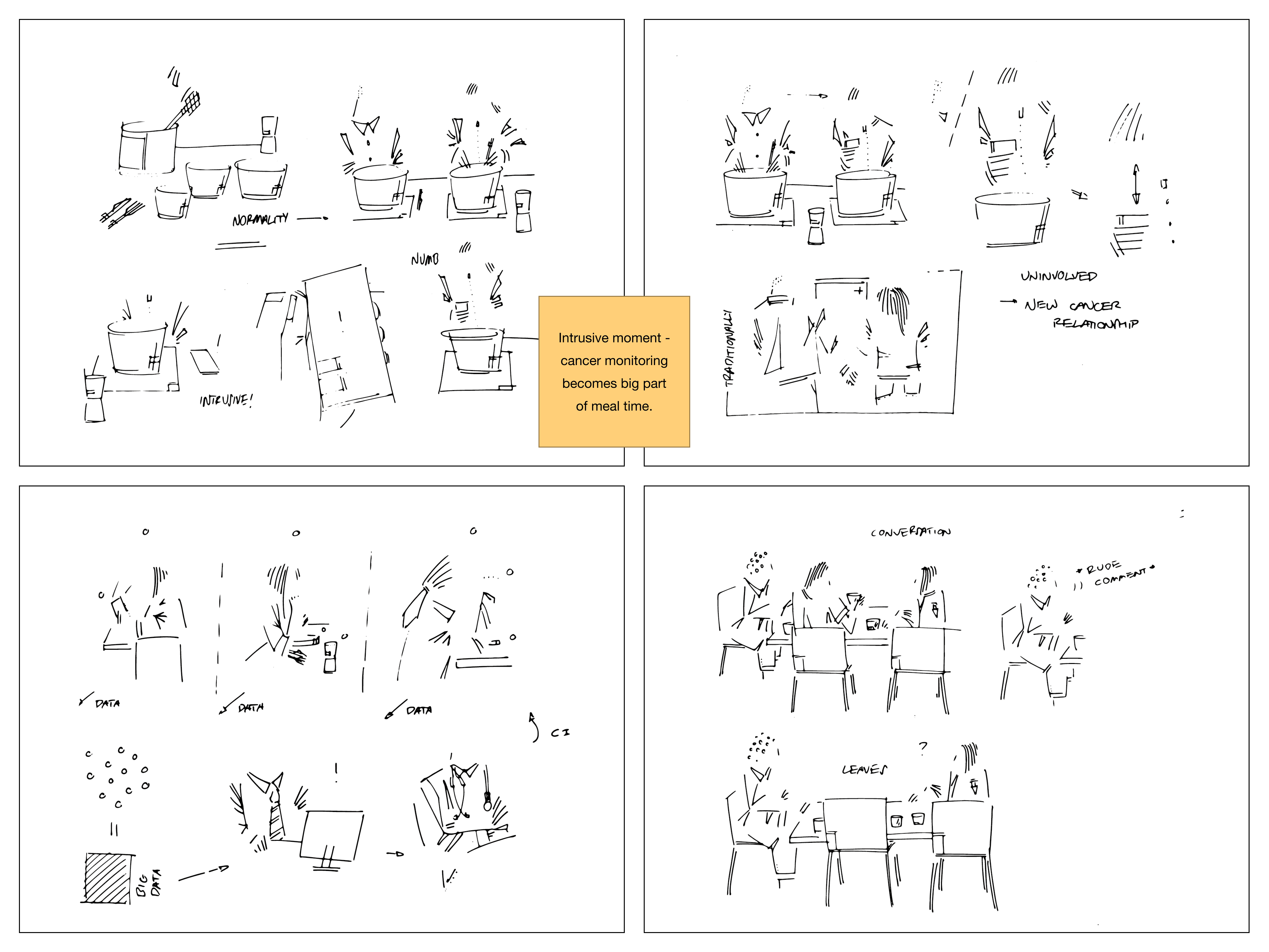

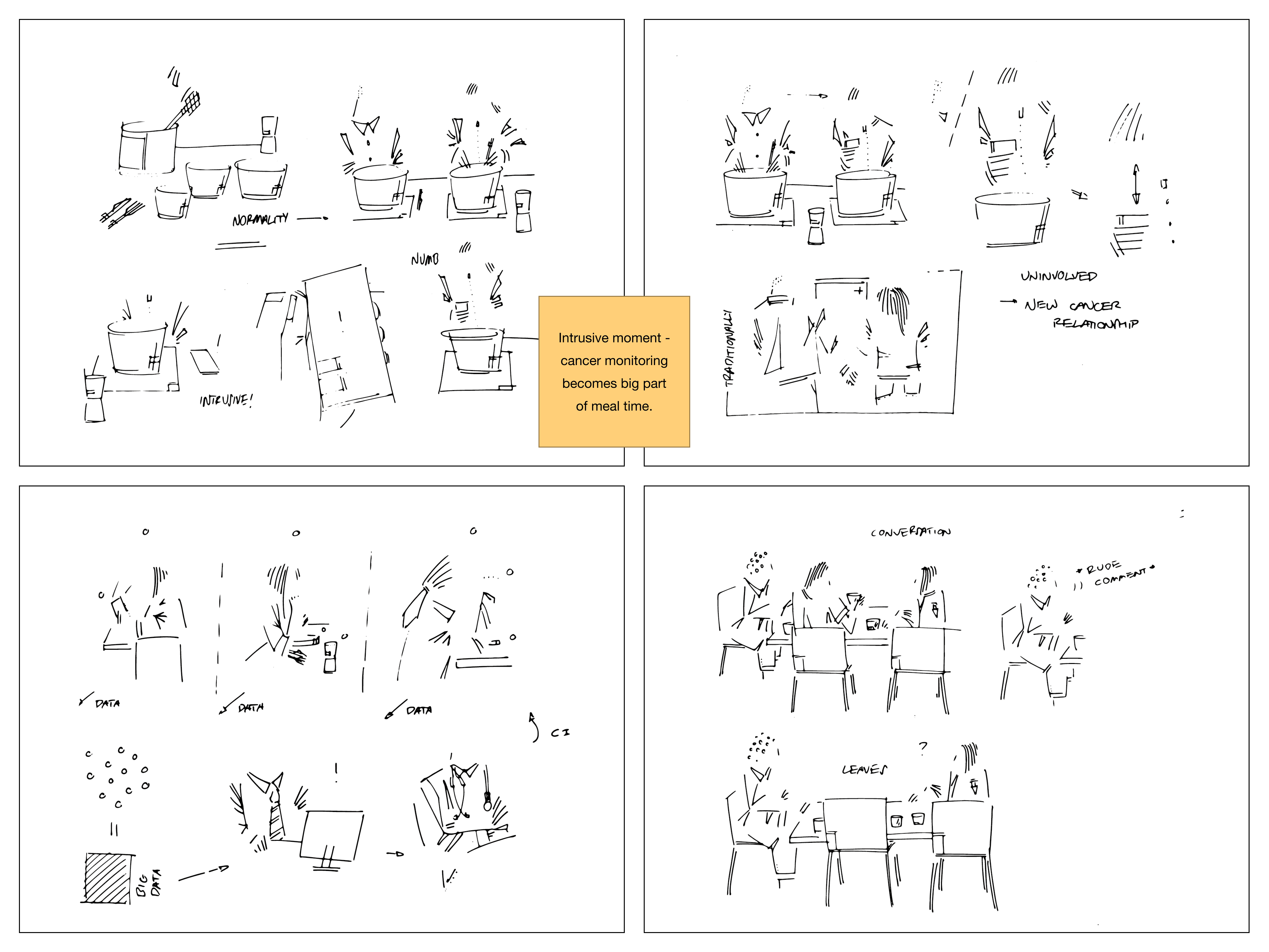

To refine this scenario we created user journeys - outlining the involved actions, stakeholders and artefacts. These started as post-its and quick sketches, and after multiple iterations ended up as a concise, explanatory storyboard.

We were then able to discuss our concept with professionals from Glasgow University’s Institute of Cancer Science, as part of an expert session. They confirmed that our idea was within reason, and reminded us to think beyond the individual user - how might the system play to many people living beyond cancer?

To refine this scenario we created user journeys - outlining the involved actions, stakeholders and artefacts. These started as post-its and quick sketches, and after multiple iterations ended up as a concise, explanatory storyboard.

We were then able to discuss our concept with professionals from Glasgow University’s Institute of Cancer Science, as part of an expert session. They confirmed that our idea was within reason, and reminded us to think beyond the individual user - how might the system play to many people living beyond cancer?

To refine this scenario we created user journeys - outlining the involved actions, stakeholders and artefacts. These started as post-its and quick sketches, and after multiple iterations ended up as a concise, explanatory storyboard.

We were then able to discuss our concept with professionals from Glasgow University’s Institute of Cancer Science, as part of an expert session. They confirmed that our idea was within reason, and reminded us to think beyond the individual user - how might the system play to many people living beyond cancer?

Deliver

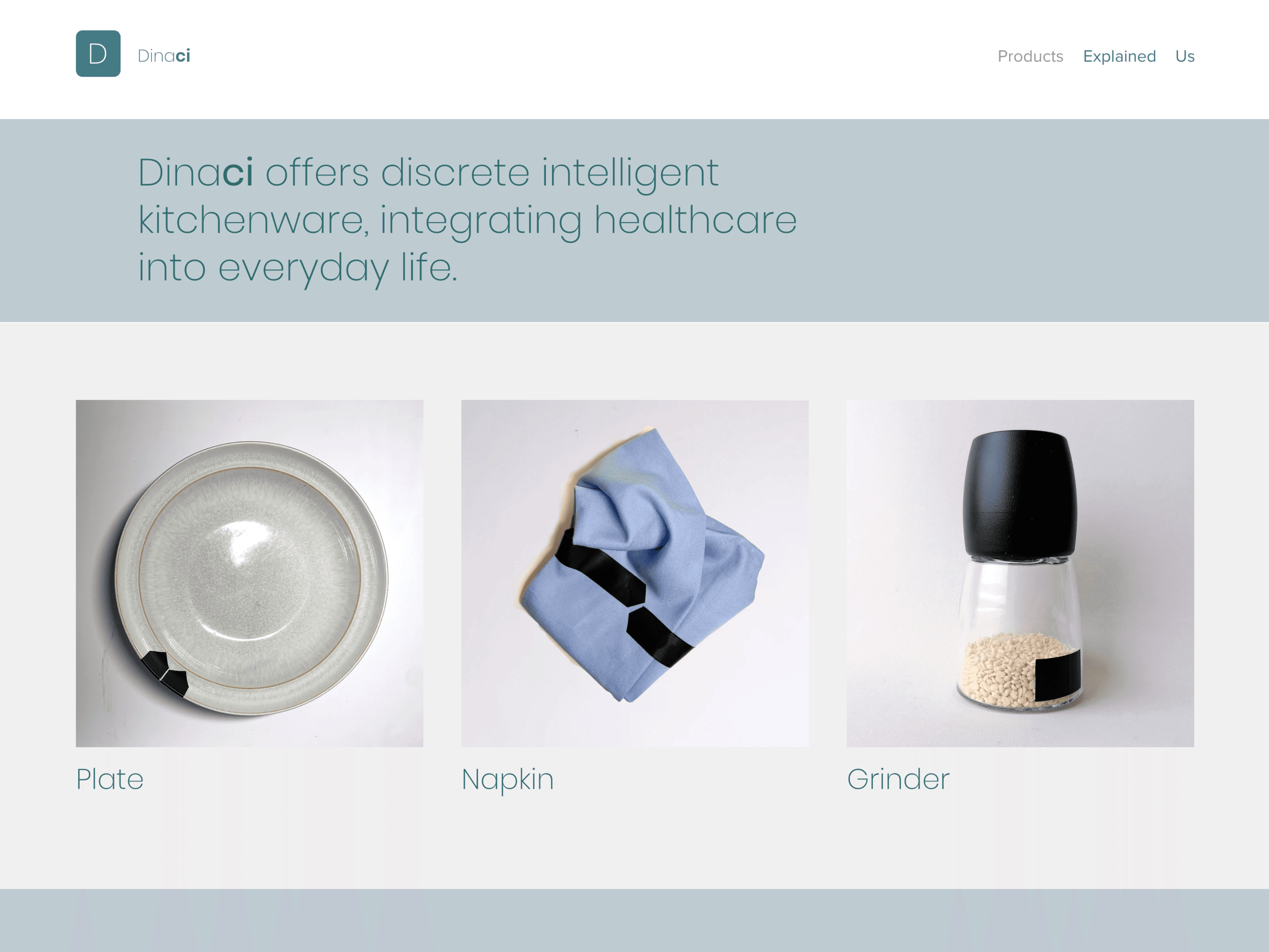

Through various workshops, input from cancer experts, mapping and ideation processes, we’d managed to refine a future experience.

We proposed a world in which technological advancements afford the integration of healthcare into everyday life. Through a set of dining artefacts, people living beyond cancer can take medicine and monitor their risk of readmission. Data gathered can then be applied in a broader context, to further inform the care of other cancer patients.

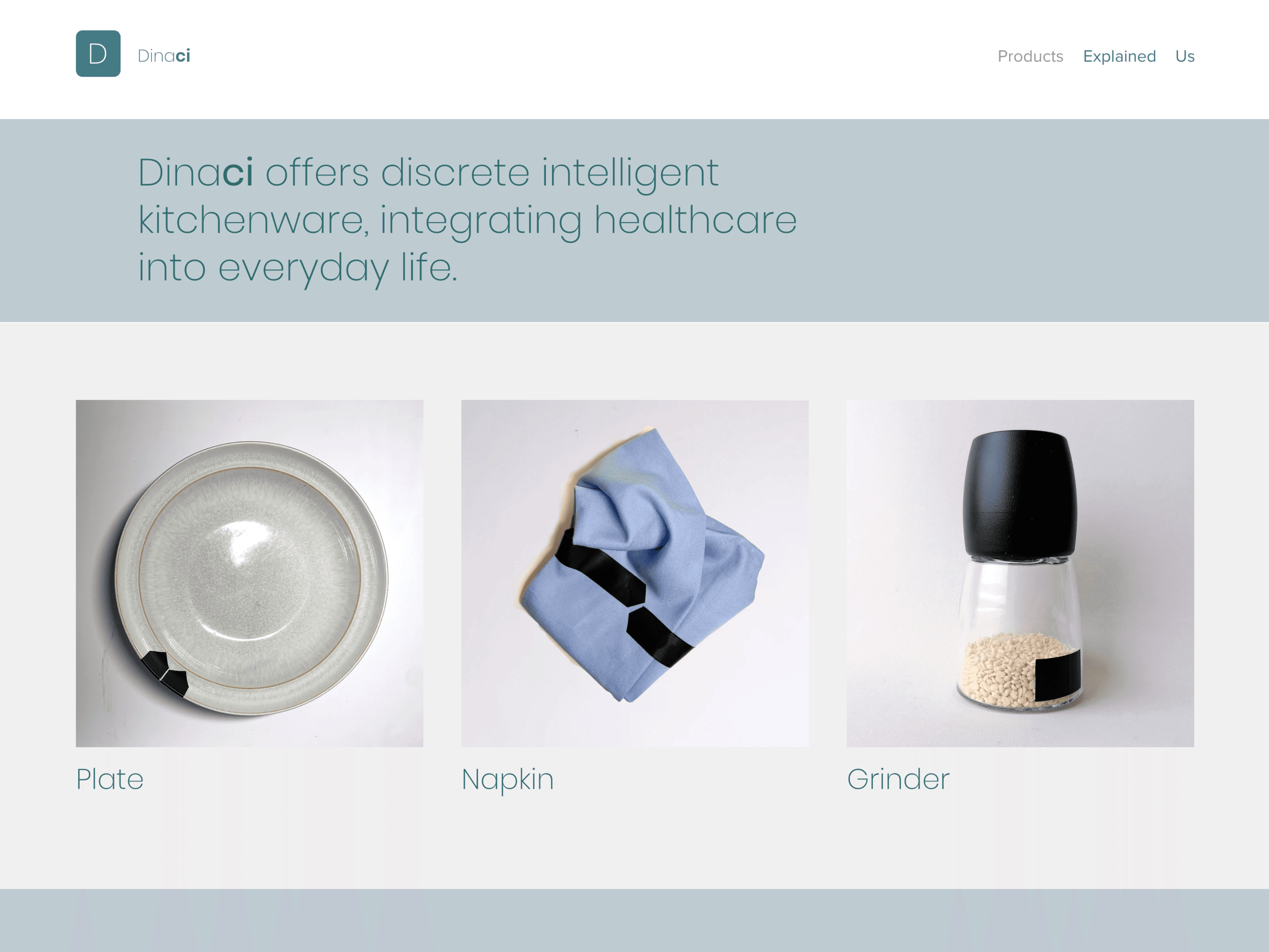

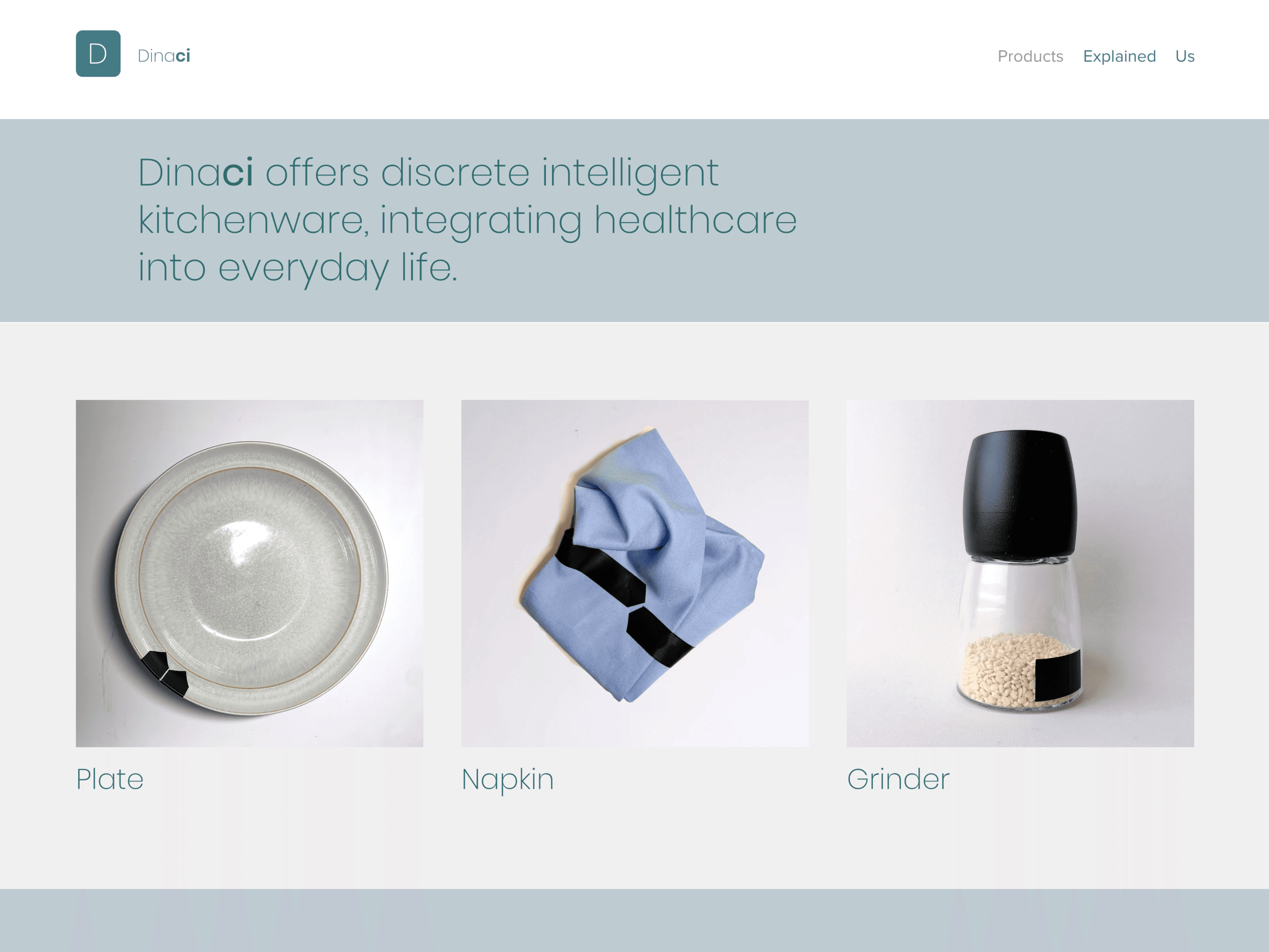

In order to explain this concept, we created a brand - Dinaci - and website to describe the service and ‘sell’ the artefacts. Since we were exhibiting virtually, due to the pandemic, this felt like a great way to share our concept.

Deliver

Through various workshops, input from cancer experts, mapping and ideation processes, we’d managed to refine a future experience.

We proposed a world in which technological advancements afford the integration of healthcare into everyday life. Through a set of dining artefacts, people living beyond cancer can take medicine and monitor their risk of readmission. Data gathered can then be applied in a broader context, to further inform the care of other cancer patients.

In order to explain this concept, we created a brand - Dinaci - and website to describe the service and ‘sell’ the artefacts. Since we were exhibiting virtually, due to the pandemic, this felt like a great way to share our concept.

Deliver

Through various workshops, input from cancer experts, mapping and ideation processes, we’d managed to refine a future experience.

We proposed a world in which technological advancements afford the integration of healthcare into everyday life. Through a set of dining artefacts, people living beyond cancer can take medicine and monitor their risk of readmission. Data gathered can then be applied in a broader context, to further inform the care of other cancer patients.

In order to explain this concept, we created a brand - Dinaci - and website to describe the service and ‘sell’ the artefacts. Since we were exhibiting virtually, due to the pandemic, this felt like a great way to share our concept.

Discover

Part two of the project involved working individually, to identify and explore a design opportunity within the future world experience.

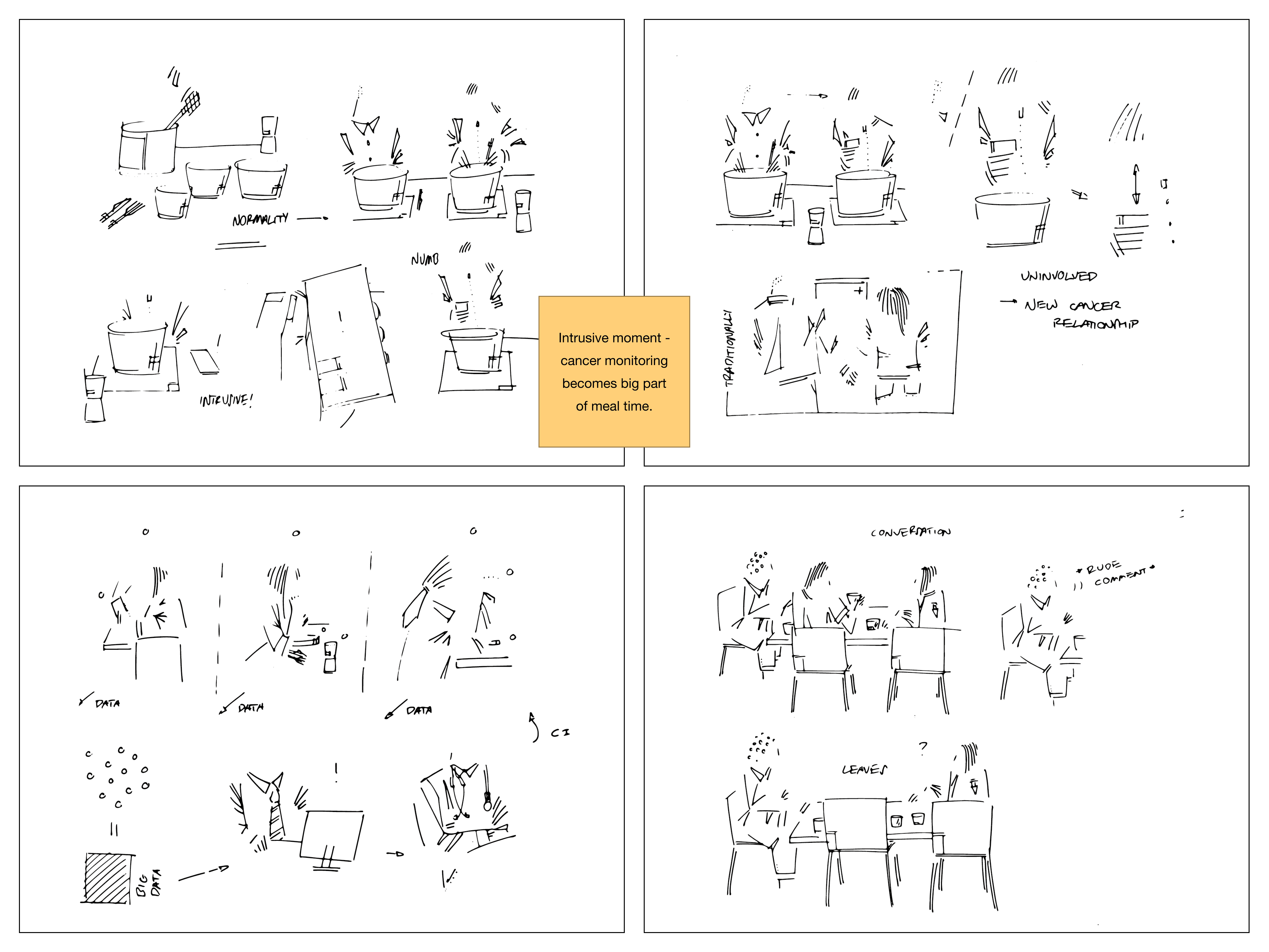

I sketched storyboards to illustrate various scenarios of living with Dinaci. In doing so, I was able to discover new dynamics between patient and system, which were not initially apparent.

I was particularly interested in the intrusive nature of having health monitoring devices in the home. This consideration felt vital, and was emphasised through discussion with the experts - who made clear the overwhelming presence that cancer has in someone’s life, even after remission.

Discover

Part two of the project involved working individually, to identify and explore a design opportunity within the future world experience.

I sketched storyboards to illustrate various scenarios of living with Dinaci. In doing so, I was able to discover new dynamics between patient and system, which were not initially apparent.

I was particularly interested in the intrusive nature of having health monitoring devices in the home. This consideration felt vital, and was emphasised through discussion with the experts - who made clear the overwhelming presence that cancer has in someone’s life, even after remission.

Discover

Part two of the project involved working individually, to identify and explore a design opportunity within the future world experience.

I sketched storyboards to illustrate various scenarios of living with Dinaci. In doing so, I was able to discover new dynamics between patient and system, which were not initially apparent.

I was particularly interested in the intrusive nature of having health monitoring devices in the home. This consideration felt vital, and was emphasised through discussion with the experts - who made clear the overwhelming presence that cancer has in someone’s life, even after remission.

Define

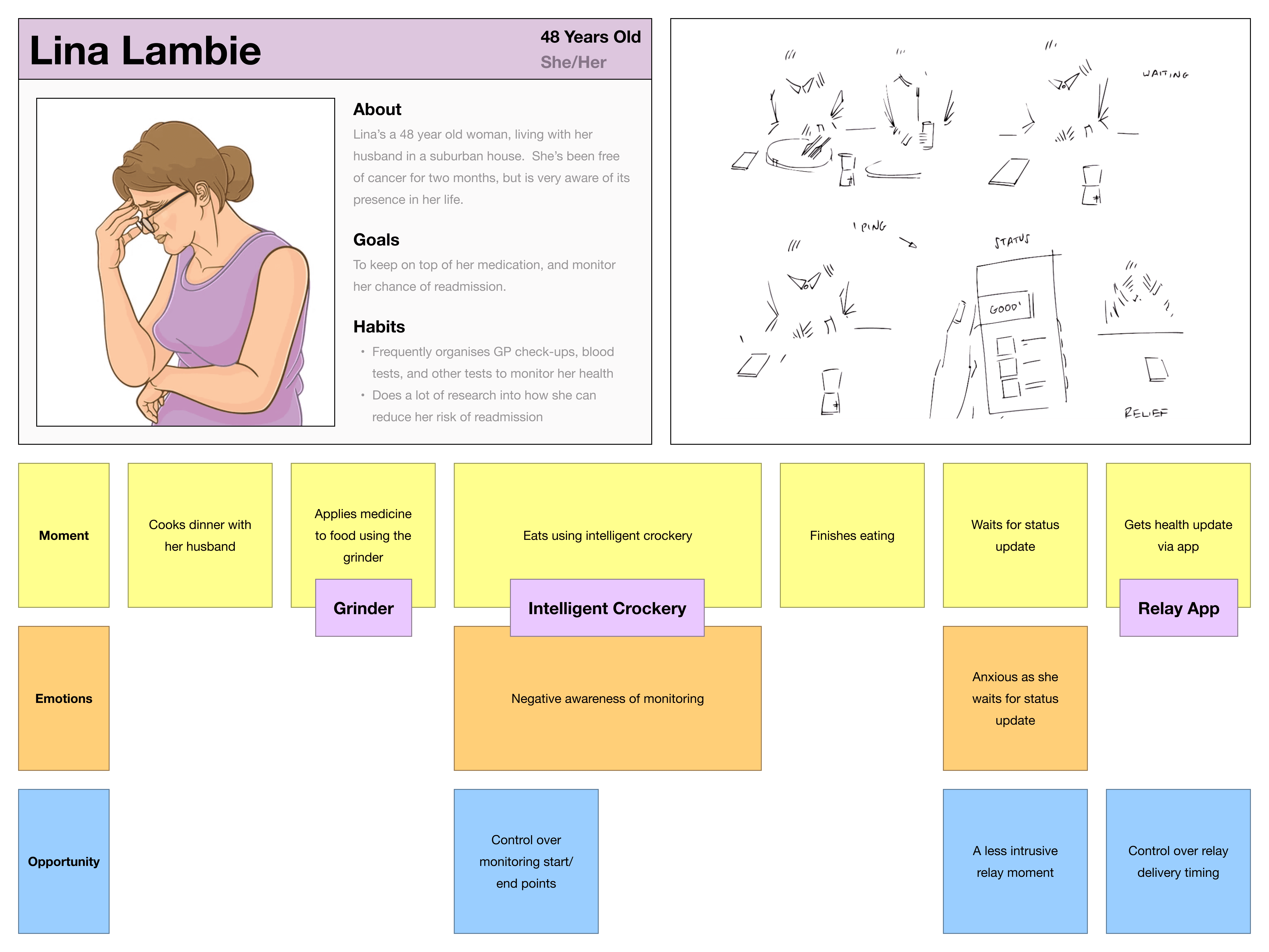

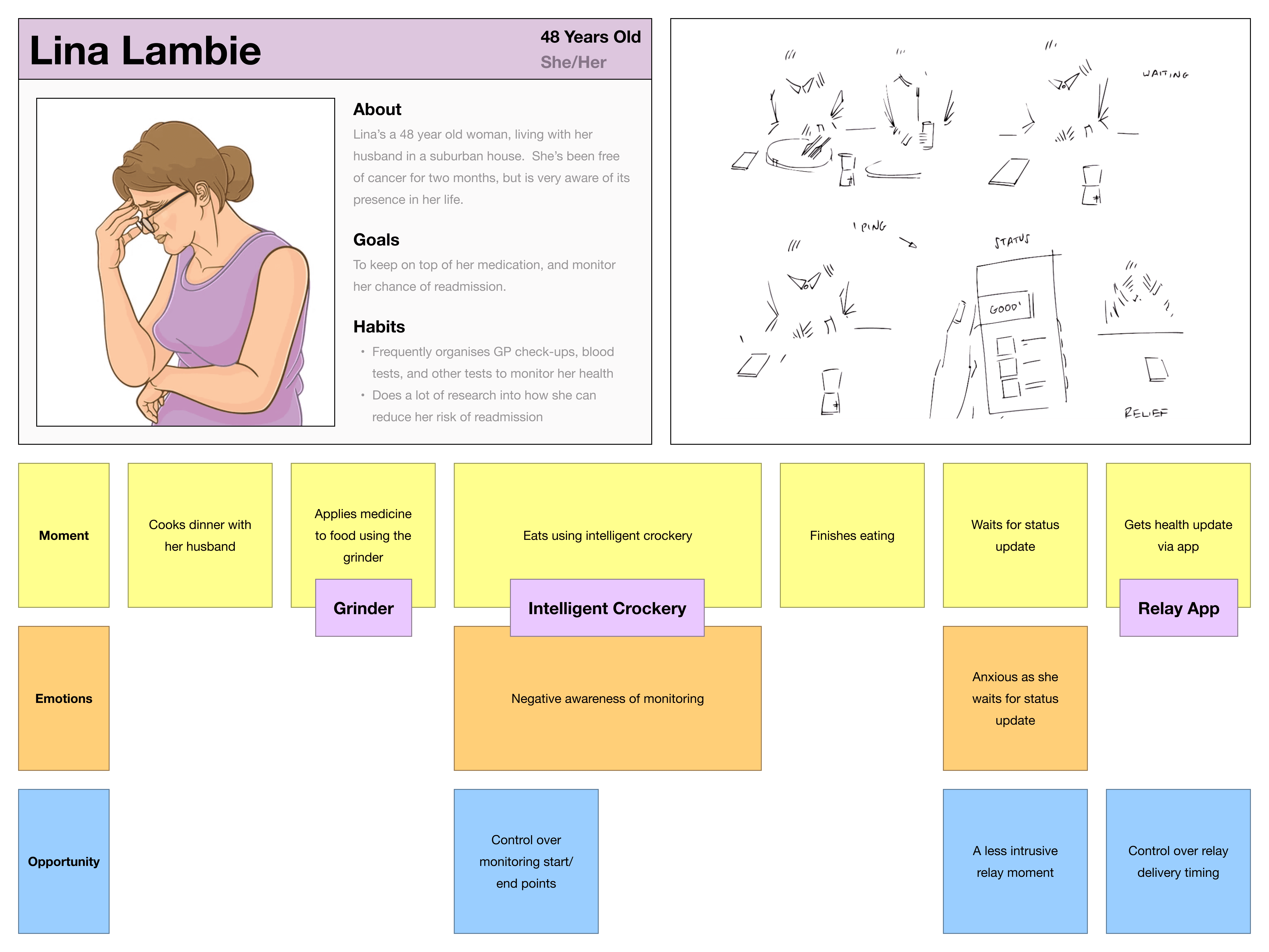

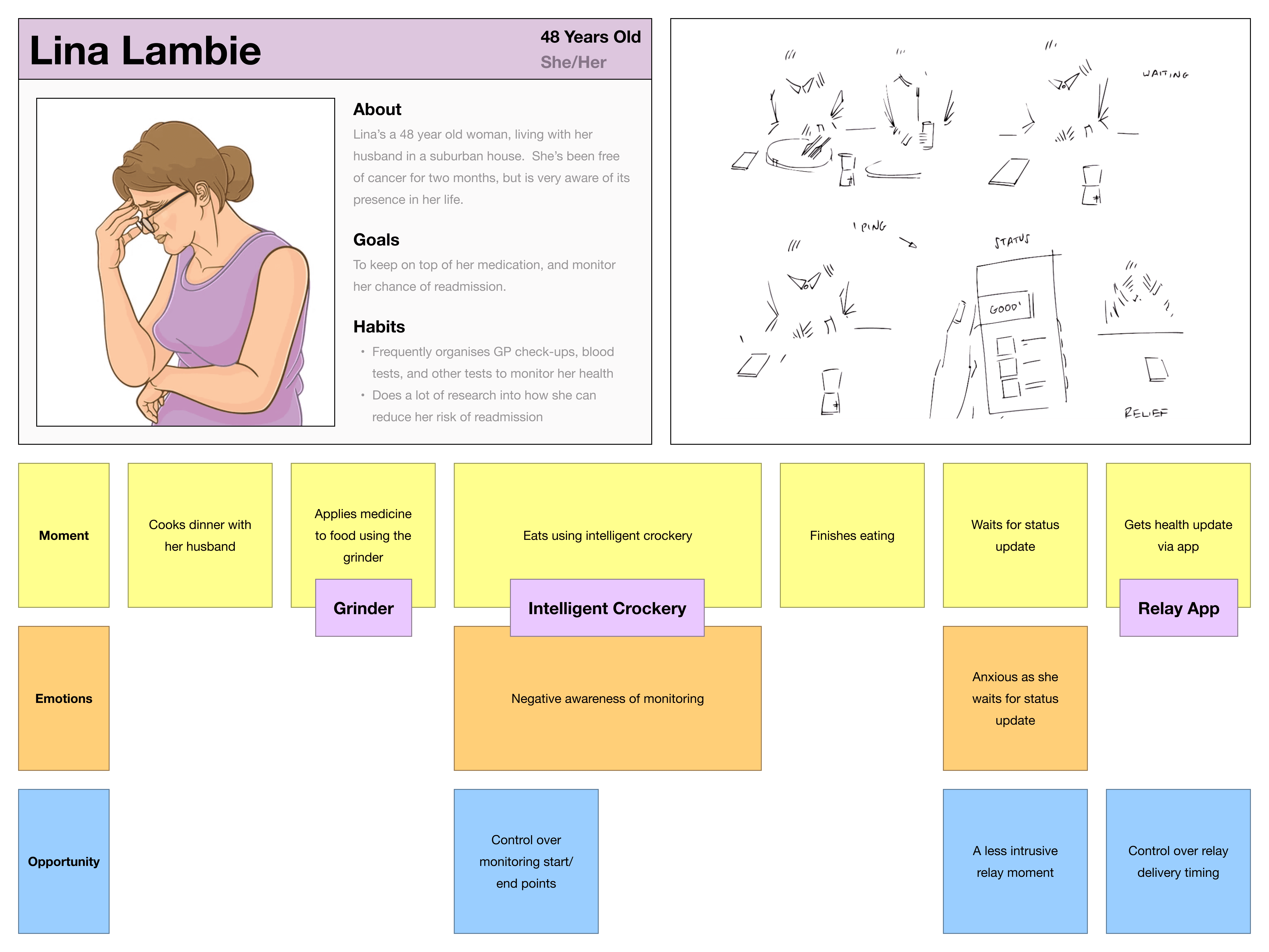

To get an understanding of how the system might intrude on the patient’s life, I created a persona. This was grounded in feedback from the experts - and illustrated a woman who struggles to detach from herself cancer, even after remission.

As a means of considering her relationship with the Dinaci system, I created a user journey - outlining the various moments and emotions that she may face as part of her experience. This helped me recognise various opportunities;

I’d consider the moment of relay - and redesign this to be less intrusive, as well as giving the patient more control over when they choose to receive this information.

I’d also think about how she could gain control over the monitoring process, specifically its start and end points.

Define

To get an understanding of how the system might intrude on the patient’s life, I created a persona. This was grounded in feedback from the experts - and illustrated a woman who struggles to detach from herself cancer, even after remission.

As a means of considering her relationship with the Dinaci system, I created a user journey - outlining the various moments and emotions that she may face as part of her experience. This helped me recognise various opportunities;

I’d consider the moment of relay - and redesign this to be less intrusive, as well as giving the patient more control over when they choose to receive this information.

I’d also think about how she could gain control over the monitoring process, specifically its start and end points.

Define

To get an understanding of how the system might intrude on the patient’s life, I created a persona. This was grounded in feedback from the experts - and illustrated a woman who struggles to detach from herself cancer, even after remission.

As a means of considering her relationship with the Dinaci system, I created a user journey - outlining the various moments and emotions that she may face as part of her experience. This helped me recognise various opportunities;

I’d consider the moment of relay - and redesign this to be less intrusive, as well as giving the patient more control over when they choose to receive this information.

I’d also think about how she could gain control over the monitoring process, specifically its start and end points.

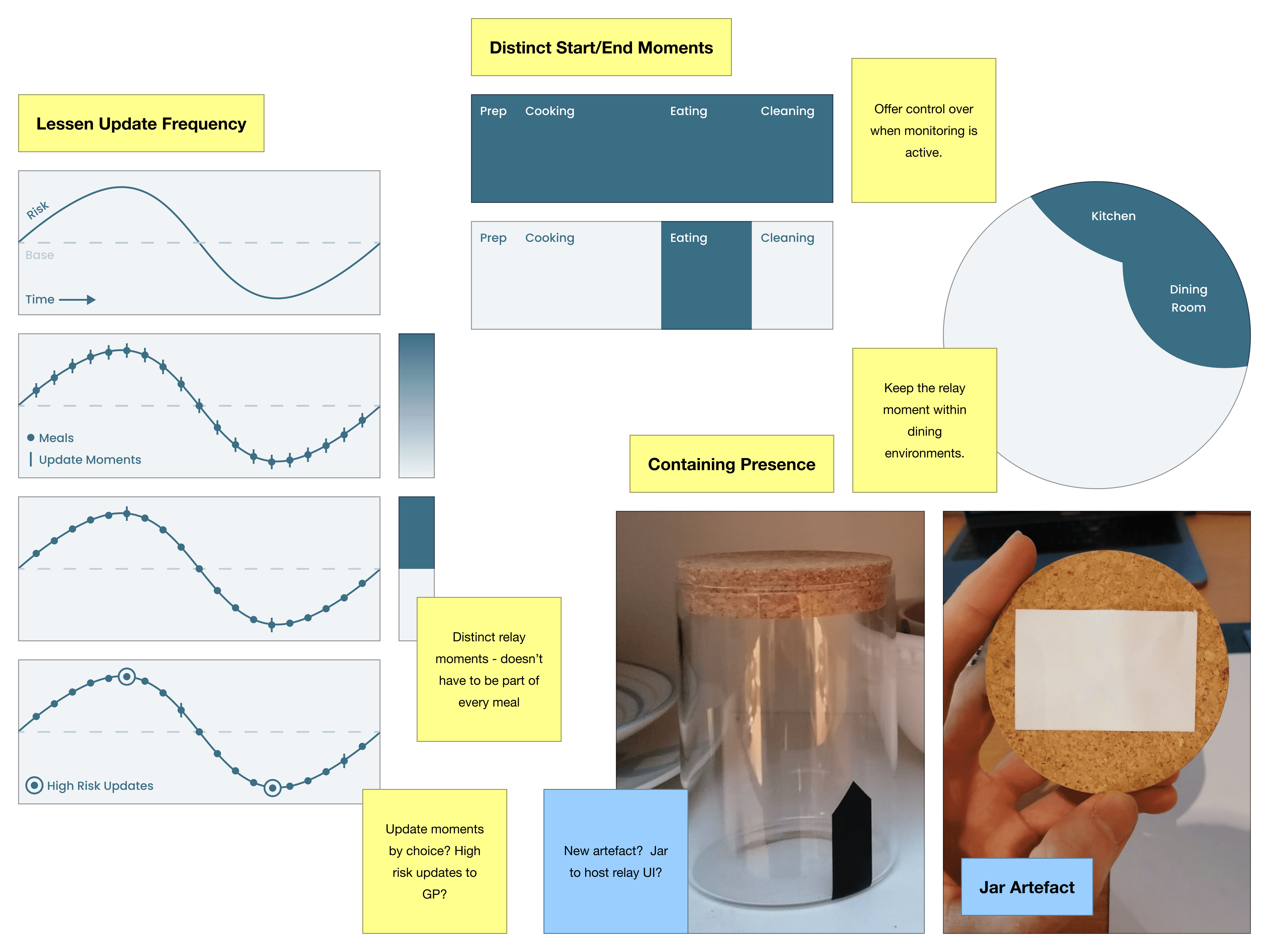

Develop

The storyboards, personas, and user journeys, I had refined opportunities for design - I’d consider the relay moment, and how the system could be more transparent in the timing of delivery and monitoring.

I began to develop ideas around this; creating lots of graphics to visualise these considerations.

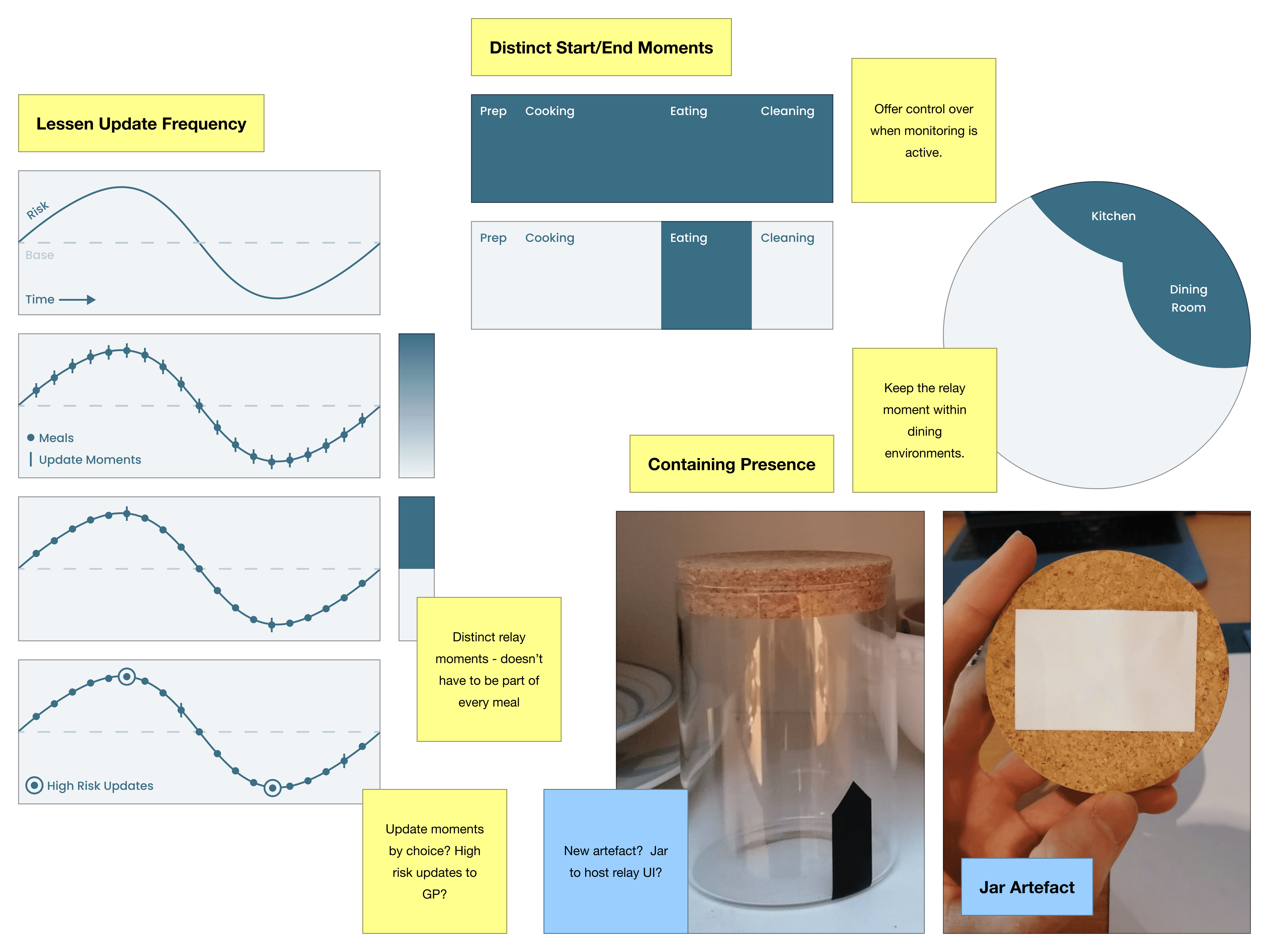

I wanted to move away from an app as the relay platform - as this is something that the user carries with them beyond the Dinaci system - allowing cancer to further intrude on their every day life, and other environments within the home.

I also wanted to consider ways in which the user could gain further control over the start and end points of the monitoring process.

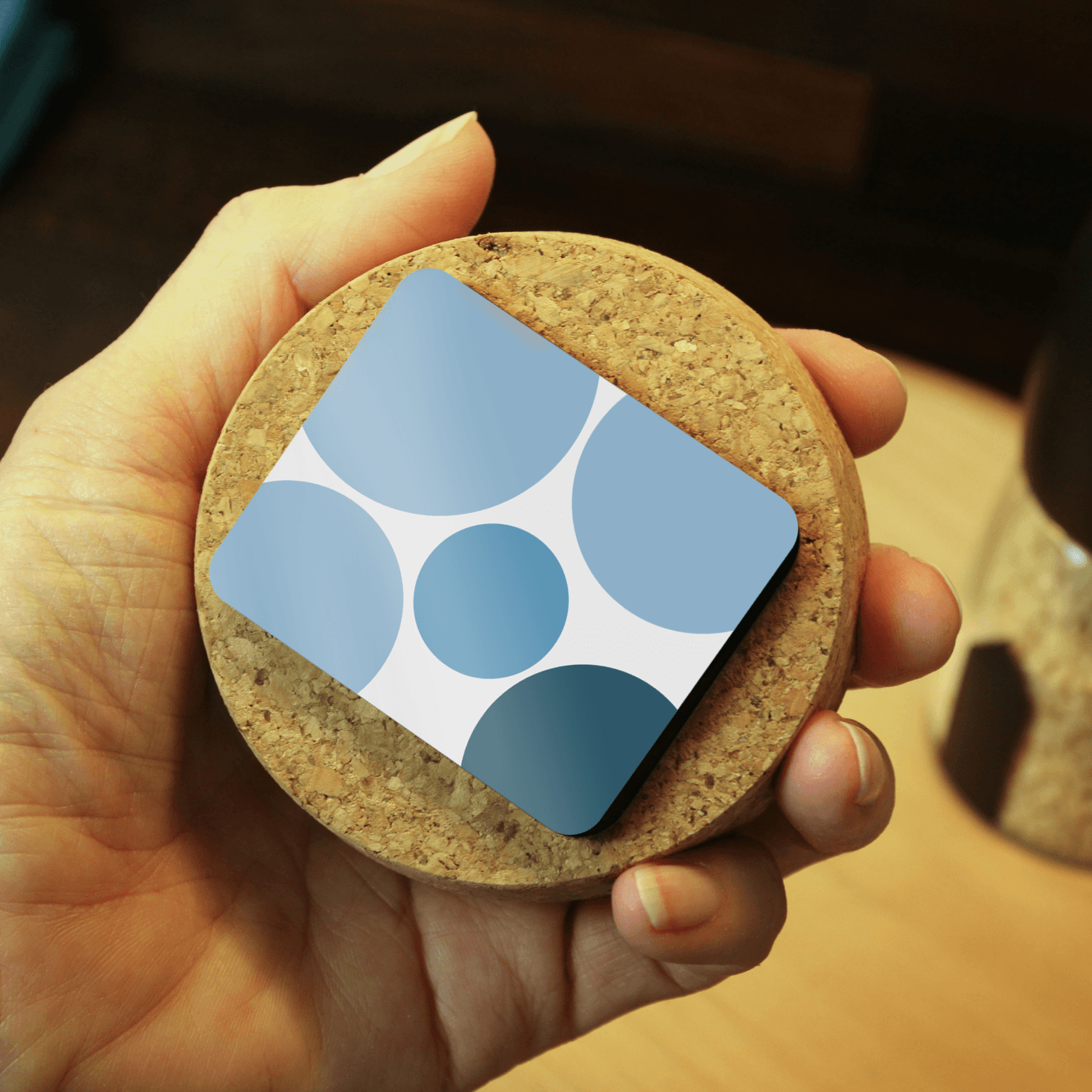

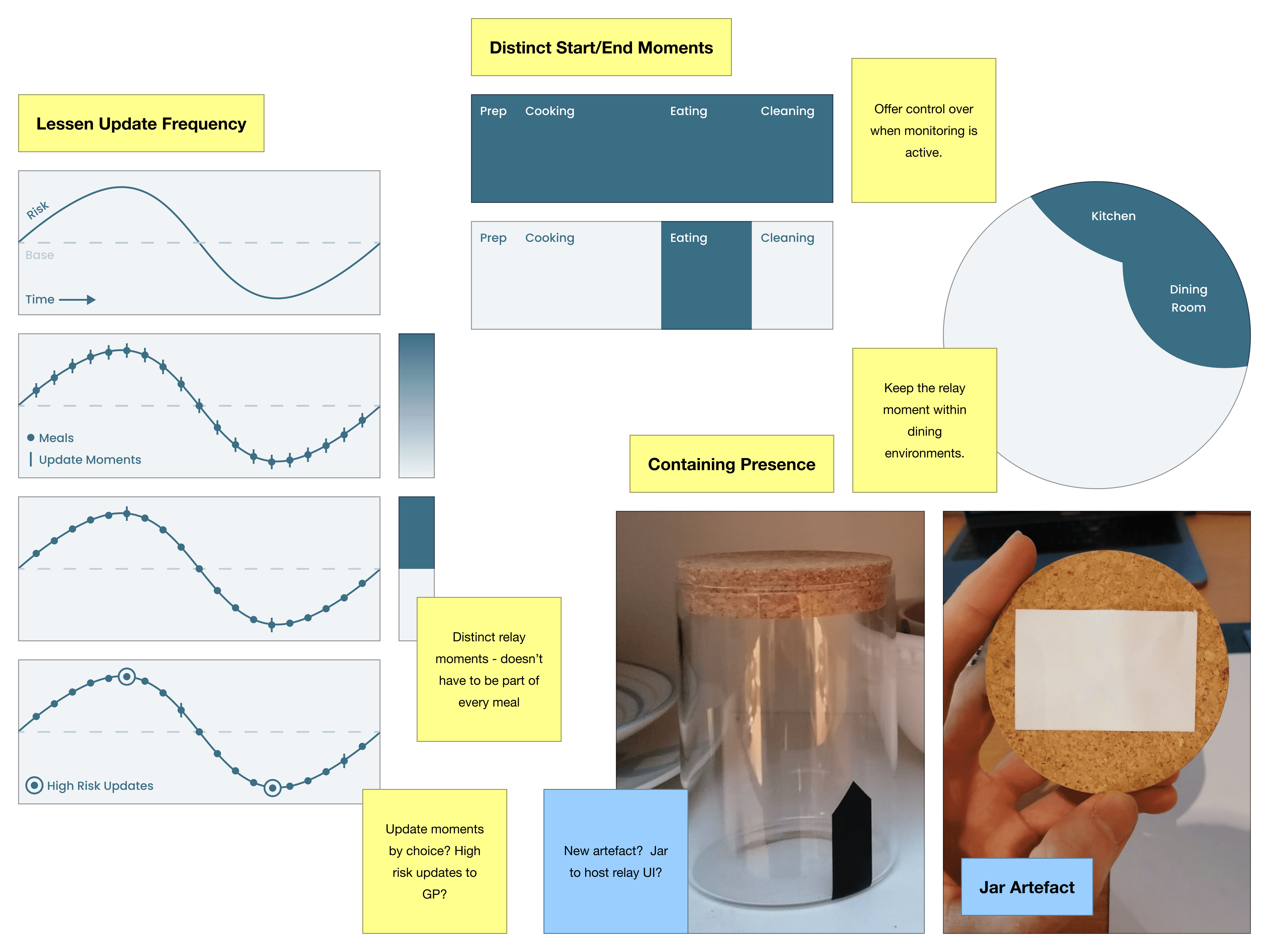

This resulted in the creation of two new artefacts - a ‘slab’ - which would be used to start and end the monitoring process, and a ‘jar’ - which would house the patients medicine, and act as the relay platform.

Develop

The storyboards, personas, and user journeys, I had refined opportunities for design - I’d consider the relay moment, and how the system could be more transparent in the timing of delivery and monitoring.

I began to develop ideas around this; creating lots of graphics to visualise these considerations.

I wanted to move away from an app as the relay platform - as this is something that the user carries with them beyond the Dinaci system - allowing cancer to further intrude on their every day life, and other environments within the home.

I also wanted to consider ways in which the user could gain further control over the start and end points of the monitoring process.

This resulted in the creation of two new artefacts - a ‘slab’ - which would be used to start and end the monitoring process, and a ‘jar’ - which would house the patients medicine, and act as the relay platform.

Develop

The storyboards, personas, and user journeys, I had refined opportunities for design - I’d consider the relay moment, and how the system could be more transparent in the timing of delivery and monitoring.

I began to develop ideas around this; creating lots of graphics to visualise these considerations.

I wanted to move away from an app as the relay platform - as this is something that the user carries with them beyond the Dinaci system - allowing cancer to further intrude on their every day life, and other environments within the home.

I also wanted to consider ways in which the user could gain further control over the start and end points of the monitoring process.

This resulted in the creation of two new artefacts - a ‘slab’ - which would be used to start and end the monitoring process, and a ‘jar’ - which would house the patients medicine, and act as the relay platform.

Deliver

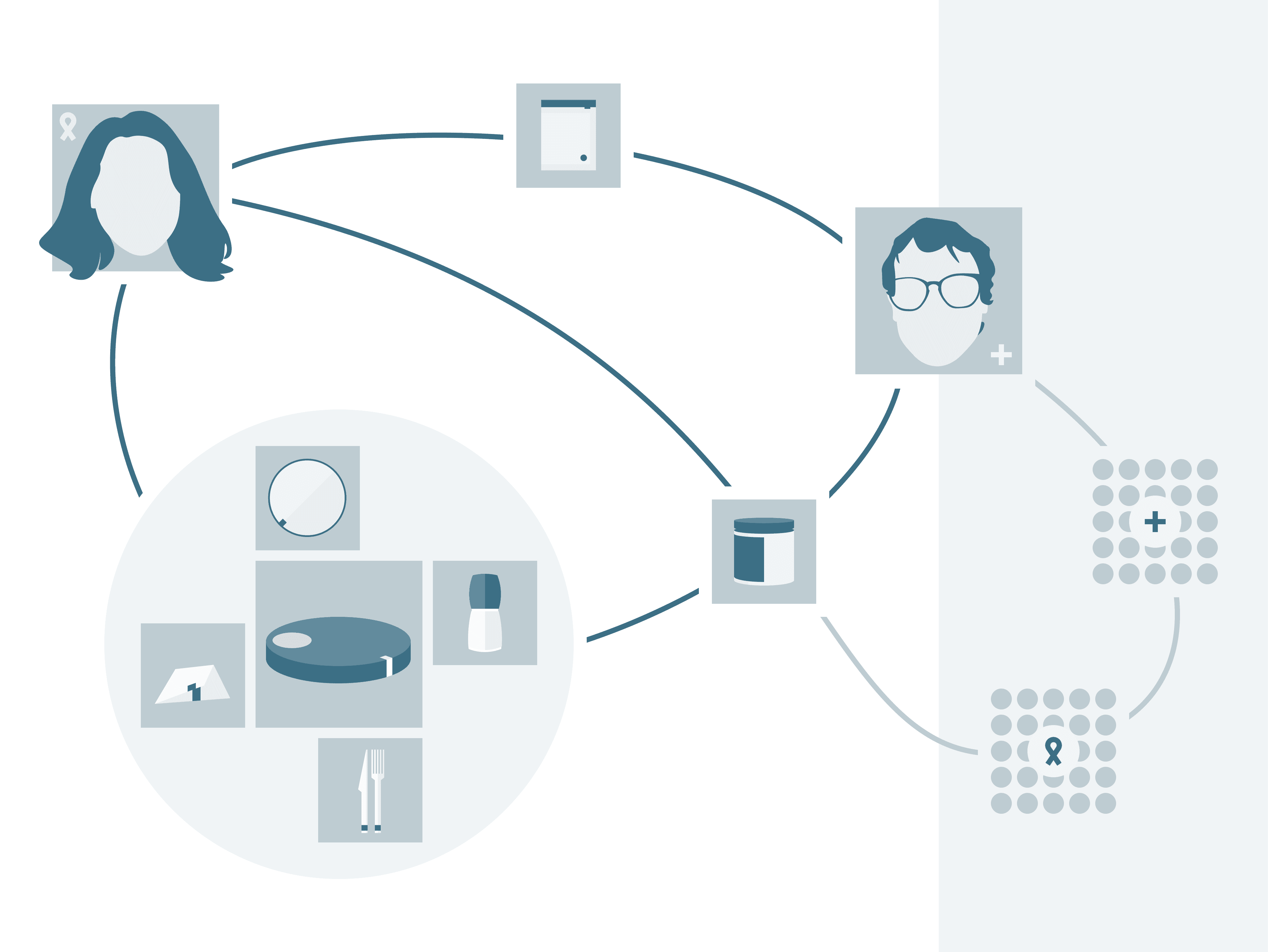

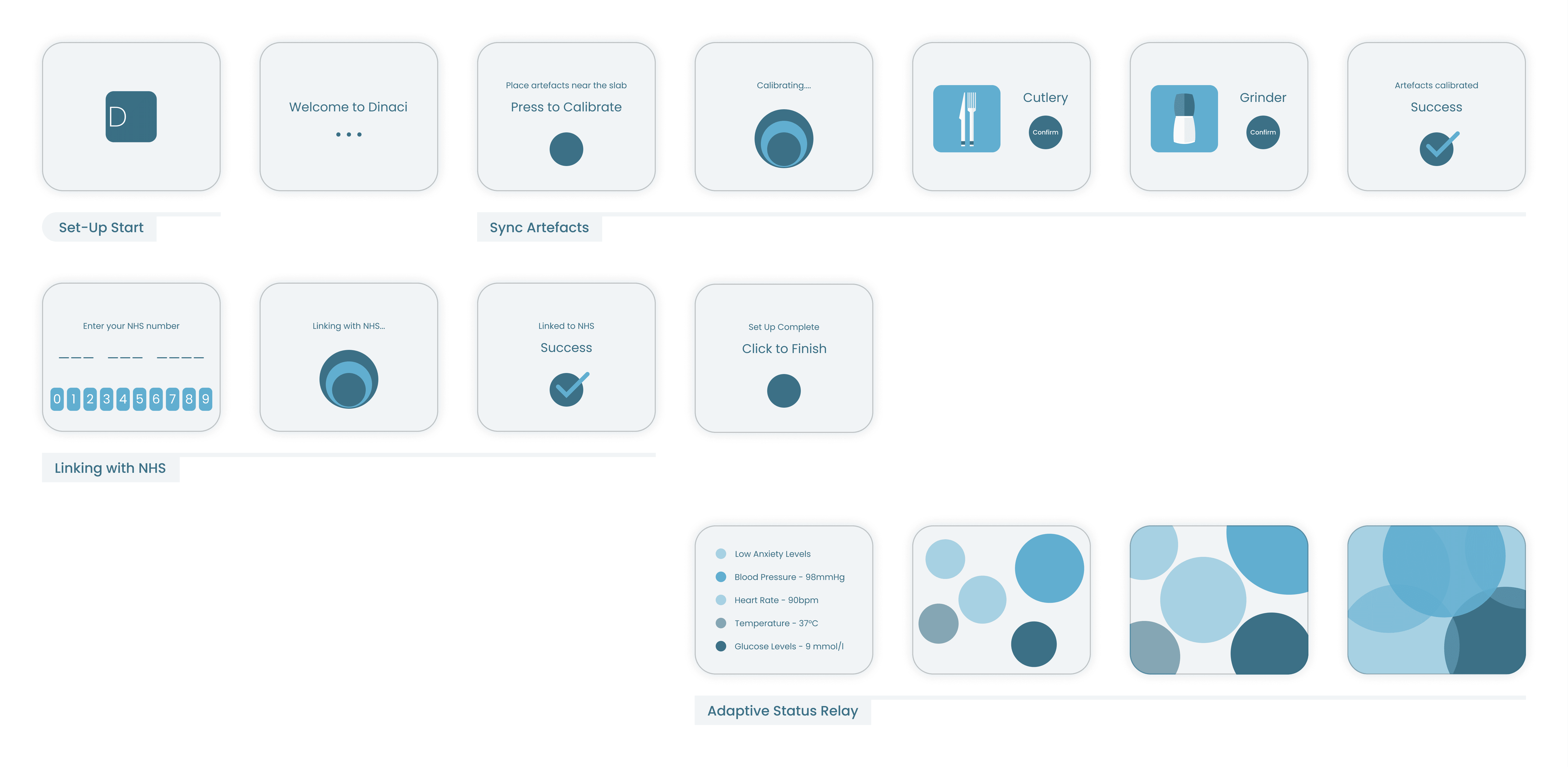

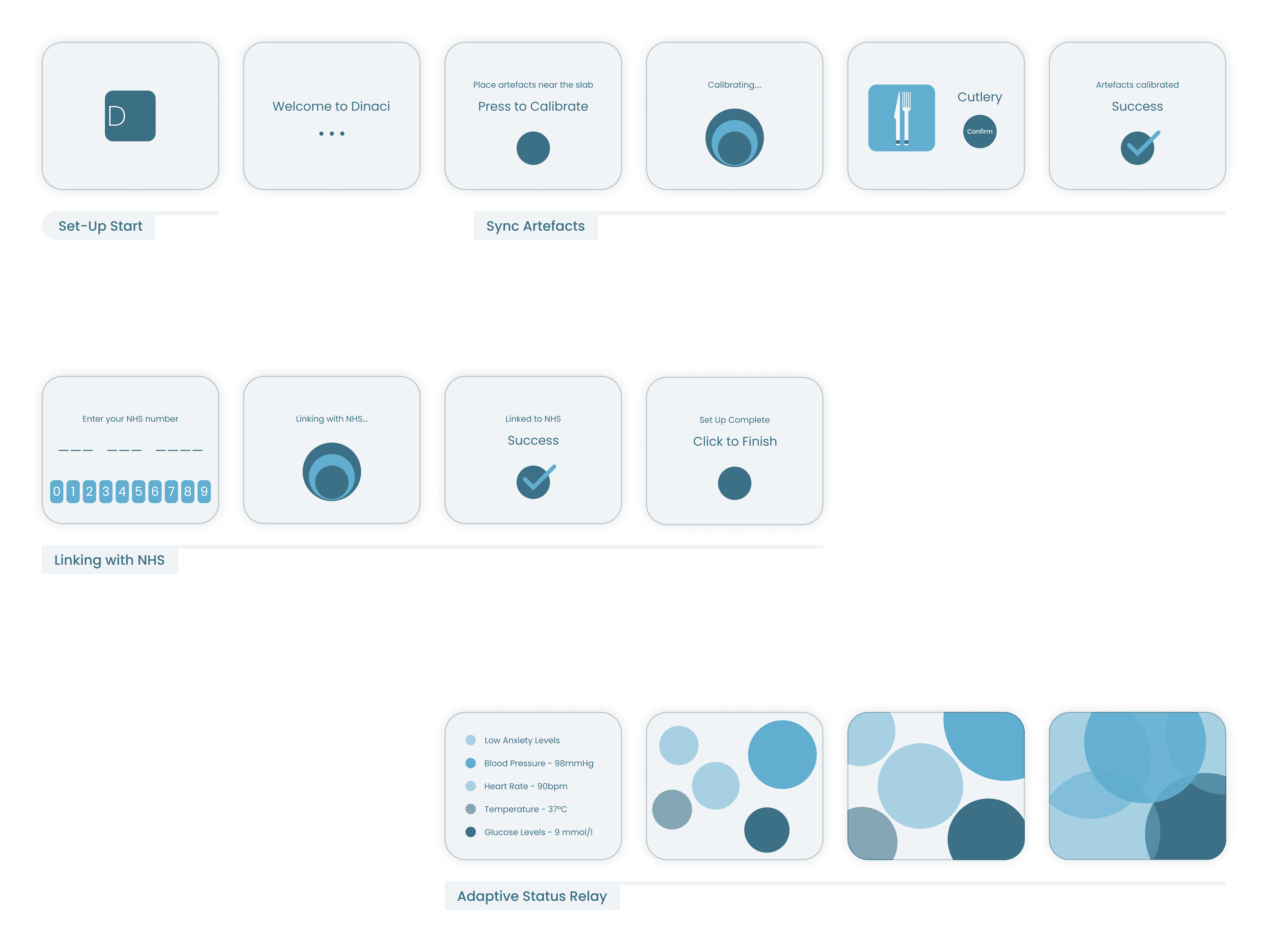

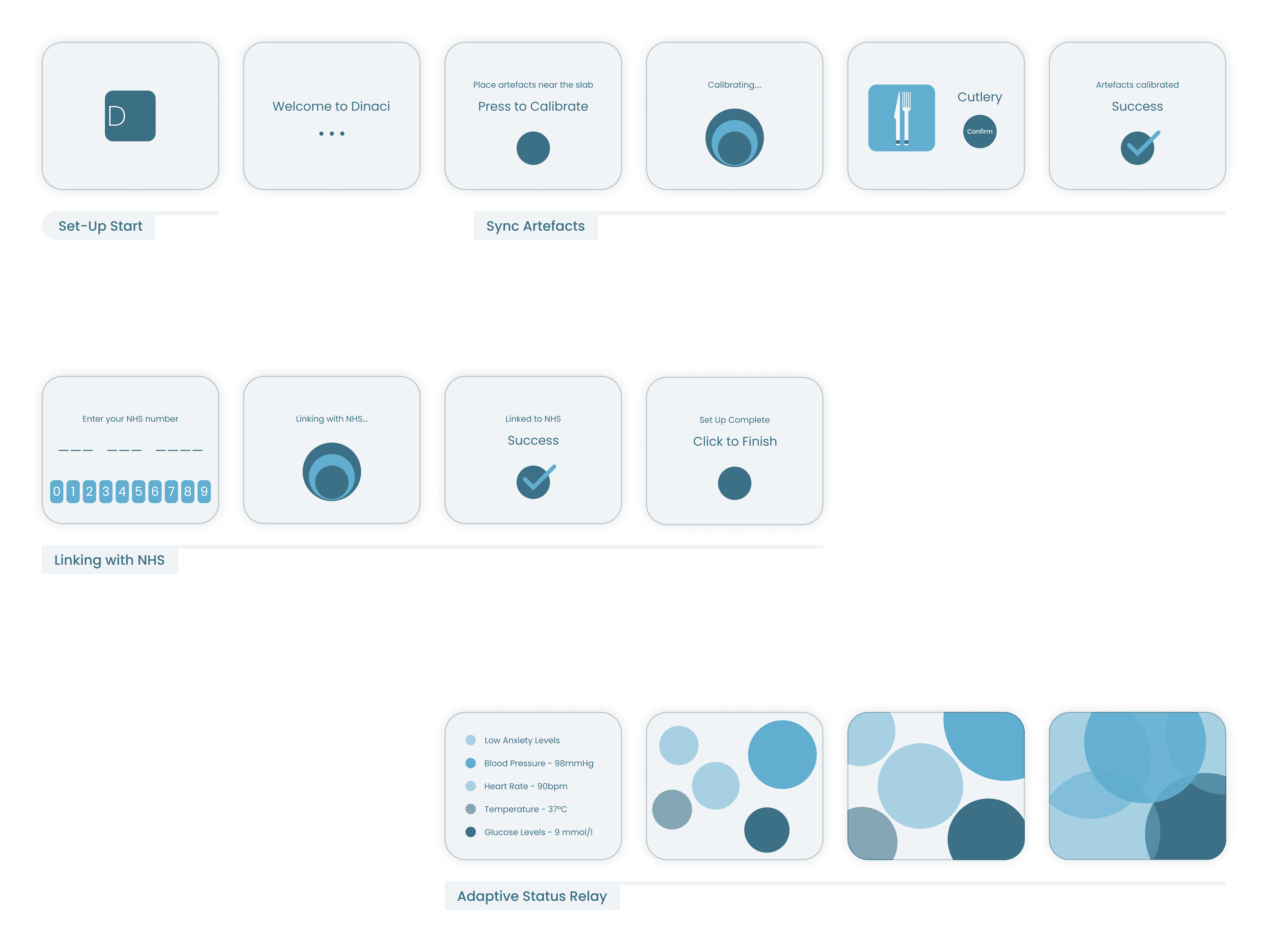

I had arrived at a final design - Dinaci, a private healthcare brand of 2030, allows people living beyond cancer to take medicine and monitor their risk of readmission from home.

Various artefacts are involved in this process - to deliver, monitor and relay - including a medicine ‘grinder’ (to deliver), ‘intelligent crockery’ (to monitor), and a ‘jar’ (to relay). This entire experience is tied together by a ‘slab’, which acts to sync and charge the artefacts, as well as to control the monitoring start and end points.

I created various materials to tell this story, including a system map, storyboard, artefacts, contextual images and a breakdown of the UI.

Deliver

I had arrived at a final design - Dinaci, a private healthcare brand of 2030, allows people living beyond cancer to take medicine and monitor their risk of readmission from home.

Various artefacts are involved in this process - to deliver, monitor and relay - including a medicine ‘grinder’ (to deliver), ‘intelligent crockery’ (to monitor), and a ‘jar’ (to relay). This entire experience is tied together by a ‘slab’, which acts to sync and charge the artefacts, as well as to control the monitoring start and end points.

I created various materials to tell this story, including a system map, storyboard, artefacts, contextual images and a breakdown of the UI.

Deliver

I had arrived at a final design - Dinaci, a private healthcare brand of 2030, allows people living beyond cancer to take medicine and monitor their risk of readmission from home.

Various artefacts are involved in this process - to deliver, monitor and relay - including a medicine ‘grinder’ (to deliver), ‘intelligent crockery’ (to monitor), and a ‘jar’ (to relay). This entire experience is tied together by a ‘slab’, which acts to sync and charge the artefacts, as well as to control the monitoring start and end points.

I created various materials to tell this story, including a system map, storyboard, artefacts, contextual images and a breakdown of the UI.